By Geraint John and Daniel Karns

Solar panels (and the solar panel supply chain) have an important role to play in the global transition to clean energy, but China’s use of forced labor to produce key components represents a tangible supply chain risk for U.S.-based companies.

Polysilicon – an essential material in the solar photovoltaic supply chain – is one of three items specifically targeted by the Uyghur Forced Labor Prevention Act (UFLPA), which took effect in June. It gives U.S. Customs and Border Protection (CBP) officers the right to detain imported products suspected of being made or partly made in the Xinjiang region of China.

A delayed and much-anticipated report on the situation in Xinjiang published in August by the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights accused China of “serious human rights violations” that “may constitute international crimes”.

As of the end of September – three months into implementation of the UFLPA – CBP commissioner Chris Magnus said that almost half of the 3,000-plus shipments detained by his agency were covered by the new law, with an estimated value of nearly $500 million. He didn’t specify the products affected, but several leading Chinese solar panel suppliers are reported to have had shipments detained or sent back.

Failing to comply with the UFLPA, knowingly or otherwise, presents serious financial, operational and reputational risks for American solar energy and other firms that need to be addressed.

China Continues to Dominate the Solar Supply Chain

Xinjiang, which is home to the predominantly Muslim ethnic minority Uyghur population, produces about 40% of the world’s supply of polysilicon, a high-purity grade of silicon mined from quartz. This is cast into ingots, which are then cut into wafers and used to make the solar cells that are, in turn, assembled into finished panels (modules).

Action by successive U.S. administrations over the past decade has largely halted the direct import of these products from China:

- Starting in March 2012, the U.S. Department of Commerce imposed tariffs of up to 165% on Chinese solar cells and panels in an effort to stop the dumping of low-cost products into the U.S. market. These measures were ratified and extended in 2014, 2018 and in February of this year.

- In June 2021, the U.S. Department of Labor added polysilicon from Xinjiang to its annually updated List of Goods Produced by Child Labor or Forced Labor. It joins nine other product groups thought to involve the use of forced labor in the region, including cotton, tomatoes, footwear and textiles.

- Later that same month, the CBP issued a Withhold Release Order (WRO) against Hoshine Silicon Industry Co. Ltd, a Xinjiang-based firm accused of using intimidation, threats and restricted movement practices against its workforce. The WRO instructs U.S. port officers to detain shipments of silica-based products made by the company and its subsidiaries.

The U.S. Solar Panel Supply Chain

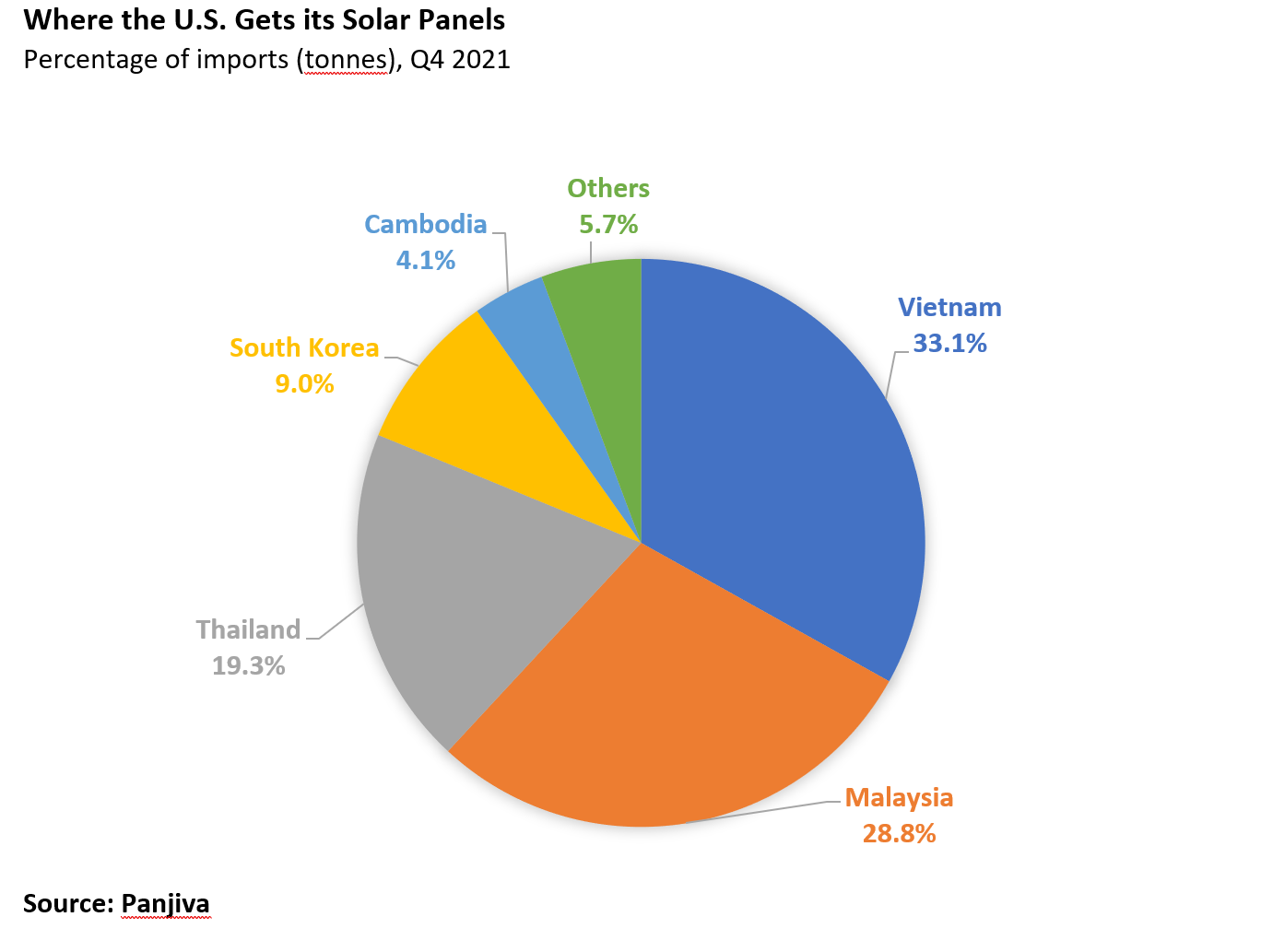

As a result of these actions, U.S. imports of solar panels now come mainly from other countries in Asia. In the final quarter of 2021, Vietnam, Malaysia and Thailand accounted for more than 80% of shipments (see chart).

However, as with lithium-ion batteries, China dominates solar supply chains. Seven of the world’s 10 biggest solar panel makers are Chinese, and according to U.S. government agencies:

- China owns 72% of global manufacturing capacity for polysilicon (with 54% of total output produced in Xinjiang).

- In addition, China controls 98% of global manufacturing capacity for ingots, 97% for solar wafers, 81% for solar cells and 77% for solar panels.

- Three-quarters of solar cells installed in the U.S. are made by subsidiaries of Chinese firms operating in Vietnam, Malaysia and Thailand, which import large quantities of solar materials from China.

An analysis of Interos’ global relationship platform data in August found:

- 120 direct, tier-1 relationships between U.S. buyers and Chinese solar panel suppliers.

- Almost 9,500 indirect, tier-2 relationships, with the vast majority accounted for by four suppliers: JinkoSolar Holding Co. Ltd; JA Solar Holdings Co. Ltd; Trina Solar Co. Ltd; and Suntech Power Holdings Co. Ltd.

- Hoshine Silicon Industry Co. Ltd – the subject of last year’s WRO action – had just five direct relationships with U.S. buyers, but more than 160 tier-2 connections.

Guilty Until Proven Innocent

Unlike some previous supply chain-oriented legislation, the UFLPA puts on the onus on importers to demonstrate that solar products have not involved the use of forced labor.

In its guidance to importers, CBP notes that “imports of all goods, wares, articles, and merchandise mined, produced, or manufactured wholly or in part in the Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region (Xinjiang) of the People’s Republic of China (PRC), or by entities identified by the U.S. government on the UFLPA Entity List, are presumed to be made with forced labor and are prohibited from entry into the United States.”

It continues: “The presumption also applies to goods made in, or shipped through, the PRC and other countries that include inputs made in Xinjiang.”

Mapping solar supply chains is therefore an essential foundation for companies to comply with the UFLPA. Speaking to Bloomberg earlier this month, AnnMarie Highsmith, an executive assistant commissioner at CBP, said companies needed tools to identify potential forced labor in their supply chains and avoid unwitting violations of the act.

A particular danger here is “supply chain washing” – where suppliers seek to avoid the UFLPA and other trade restrictions by routing raw materials, components and finished products tainted by forced labor through intermediary countries.

What can you do to safeguard your solar panel supply chain?

Alongside mapping and monitoring activities, CBP’s guidance document stipulates the following in relation to polysilicon:

- “Importers need to provide complete records of transactions and supply chain documentation that demonstrate all entities involved in the manufacture, manipulation, or export of a particular good, and the country of origin of each material used in the production of the products going back to the suspected source of forced labor, i.e., production in Xinjiang or by an entity on the UFLPA Strategy entities lists.

- “Provide a flow chart mapping each step in the procurement and production of all materials and identify the region where each material in the production originated (e.g., from location of the quartzite used to make polysilicon, to the location of manufacturing facilities producing polysilicon, to the location of facilities producing downstream goods used to make the imported good).

- “Provide a list of all entities associated with each step of the production process, with citations denoting the business records used to identify each upstream party with whom the importer did not directly transact.

- “Importers should be aware that imports of goods from factories that source polysilicon both from within Xinjiang and outside of Xinjiang risk being subject to detention, as it may be harder to verify that the supply chain is using only non-Xinjiang polysilicon and that the materials have not been replaced by or co-mingled with Xinjiang polysilicon at any point in the manufacturing process.”

CBP officials acknowledge that more staff are needed to fully monitor and enforce UFLPA requirements at U.S. ports of entry. But experience from its first quarter of operation suggests that companies cannot afford to be complacent about the act, which sets a new and higher bar for supply chain risk management.