By Nicolas de Zamaróczy

Hundreds of thousands of American and European companies that rely on imported products from Nigeria’s supply chain face a heightened risk of disruption as a result of the protracted political and economic crisis gripping the country.

A presidential election held on February 25th proved contentious, with widespread irregularities in voting and significant violence. The national election commission declared on March 1st ruling party candidate Bola Tinubu as the winner with 36.6% of the votes cast. However, opposition parties have thus far refused to accept the results and called for a redo, pointing to the fact that many polling places opened late on election day. Meanwhile, the country has been reeling for months from a botched currency reform which has completely paralyzed Nigeria’s cash-dependent informal economy.

Supply Chain Management in Nigeria: Western Oil and Agricultural Firms at Risk

Many foreign companies are at risk of having their imports from Nigeria disrupted. Nigeria’s main export is petroleum, with crude oil, petroleum gas, and refined oil collectively accounting for around 86% of exports by value. However, the country’s cash cow has suffered greatly in recent years with production down to nearly half of its level in 2020.

Nigeria LNG—a natural gas joint venture between the Nigerian state and energy majors Shell, Total, and Eni—has been unable to fulfill export orders for its European customers in recent months. Nigeria’s main other exports are agricultural goods (most notably, cacao beans) and small maritime craft, both of which are at significant risk from the economic turmoil in the country.

Global relationship data in the Interos platform indicates that:

- Roughly 700 American and 400 European companies have at least one Tier 1 (T1) supplier based in Nigeria.

- More than 127,244 American companies have an affected Nigerian company indirectly in their supply chains at Tier 2 (T2), with almost 300,000 at Tier 3 (T3).

- More than 236,000 E.U. and British companies have an affected Nigerian supplier at T2, with over 510,000 at T3.

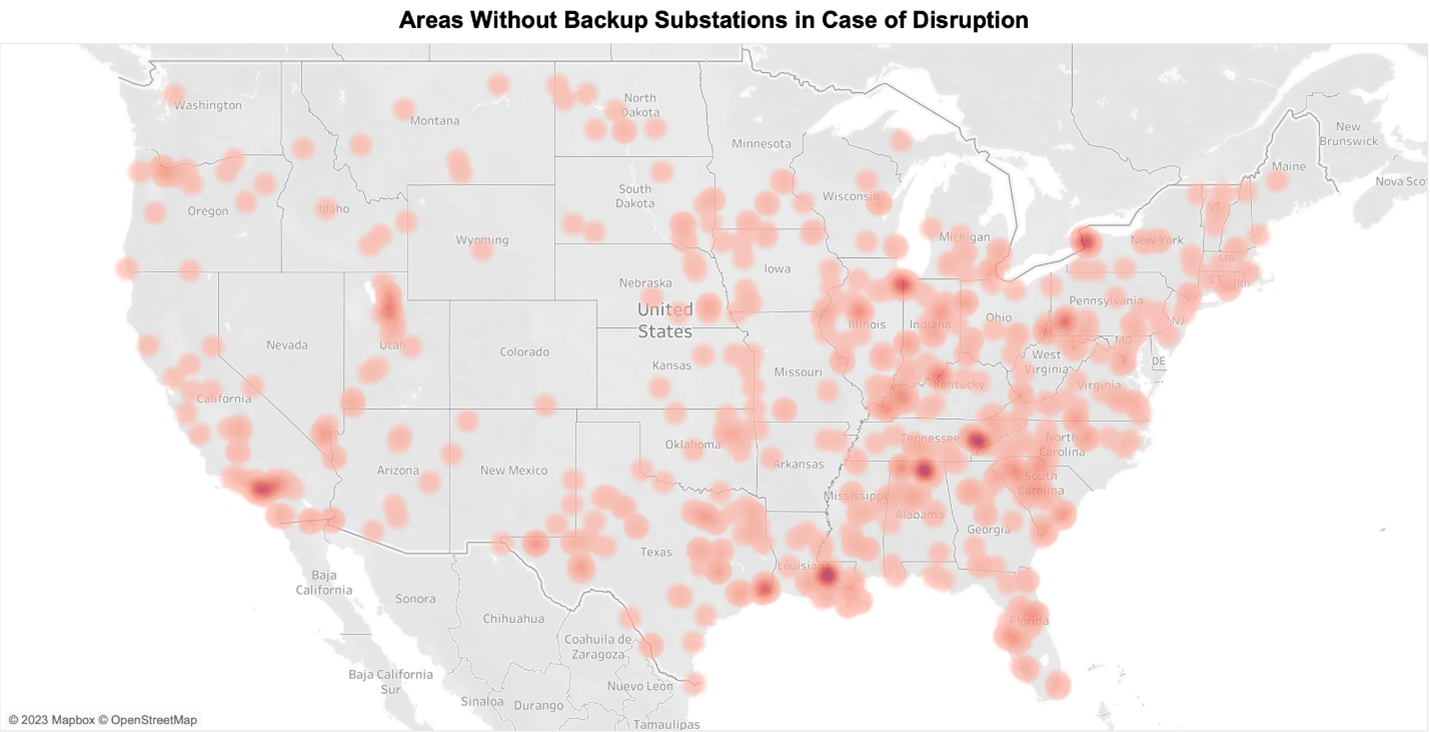

As has been the case during the last three election cycles (see chart below), Nigeria’s exports to the US had been dropping in the leadup to the election, with the volatile on-the-ground situation complicating normal operations and logistics. (The one-time surge in Nigerian exports to the US in early 2022 was due to re-routing petroleum from other destinations following the breakout of the war in Ukraine.) The lack of clarity in the presidential election suggests that low exports will continue for the foreseeable future.

Interos analysis of Panjiva data. Vertical red lines indicate prior election periods.

Nigeria’s Supply Chain Election-Related Disruptions Likely to Persist into Mid-March

Nigeria voted in a tight three-way presidential election on February 25th amidst an atmosphere of intimidation and election-related violence.

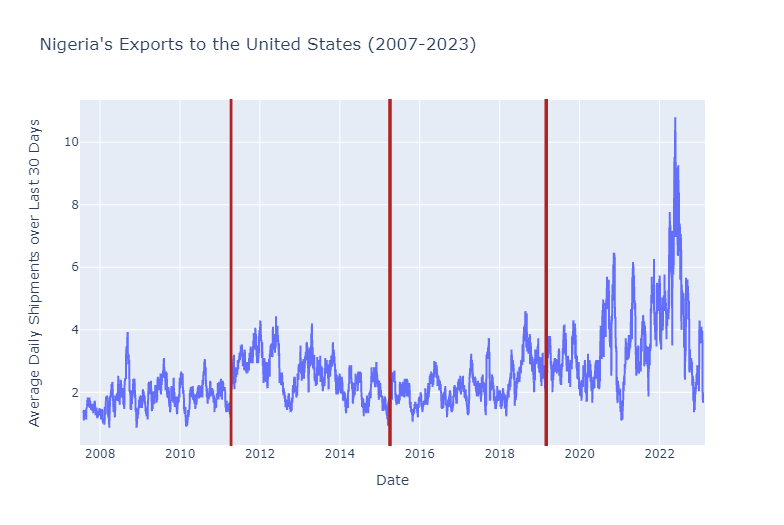

ACLED, an NGO which tracks political violence, has counted at least 193 incidents of election-related violent activity since January 1st, 2022 (see map). Human rights observers have issued warnings that Nigeria has not implemented any structural reforms since 2019, when several hundred people died during the last presidential election. These warnings have taken on new urgency following the assassination of a prominent Senate candidate on February 22nd.

Locations of Election-Related Violence in Nigeria (Jan. 2022 through Feb. 2023)

![]()

Source: ACLED’s Nigeria Election Violence Tracker. Latest data available is February 17. The size of the circle indicates the number of violent events at that location, the color of the circle indicates the specific form of violence, e.g. orange = “violence against civilians” (Image Copyright: © Mapbox, © OpenStreetMap and Improve this map).

Given that state elections will not conclude until March 11th, high levels of violence and uncertainty are likely to persist through mid-March, with a consequent impact on economic activity.

“Cash Crisis” Complicates Supply Chain Management in Nigeria

As if the political chaos were not enough, Nigeria is also suffering from the aftermath of a poorly implemented currency reform. When the Nigerian central bank announced the reform in October 2022, the hope was to combat corruption by redesigning the currency bills most used by criminal organizations. But an overly aggressive window for citizens to redeem their old banknotes combined with an extremely short supply of the new banknotes has left the entire Nigerian economy effectively without cash for several months. This has pummeled the Nigerian informal sector, which according to the IMF accounts for over 50% of GDP and over 80% of employment.

- Riots have been widespread across the country, with at least 7 local bank branches being destroyed. Paradoxically, mobile payment alternatives to brick-and-mortar banking have also stopped working, overwhelmed by a surge in demand.

- Truckers have stopped accepting old currency notes, leaving cash-strapped farmers in a lurch and unable to move their goods; cacao exports have been especially hard hit.

- Foreign airlines have faced particular headaches, routinely clashing with Nigeria’s central bank over the release of their funds, leading Delta Air Lines, British Airways, and Emirates to suspend service to Nigeria in 2022.

Nigerian Exports Likely to Stay Low in the Short Term

American and European firms with Nigerian suppliers in their extended supply chains should stay wary. Interos recommends taking the following actions to promote supply chain resilience:

- Communicate frequently with key Nigerian suppliers (or suppliers you know to be reliant on Nigeria) to determine the production impacts of the election and cash crisis.

- Identify which tier-2 and tier-3 Nigerian suppliers are critical to your direct suppliers.

- Ascertain whether suppliers in Nigeria are prepared for the extended elections period and the likely disruptions it will entail.

Organizations looking to understand where the next big supply chain shock is coming from — and which suppliers they need to engage with to mitigate the impact — should consider investing in supply chain visibility and operational resilience solutions. In times of turmoil, knowing who you are connected to, and how those parties will be impacted by unfolding events, can make the difference between continuity of operations and disaster.