G7 leaders meeting in Hiroshima, Japan this past weekend were hardly short of major global issues to discuss. From Russia’s unprovoked war in Ukraine and the proliferation of nuclear weapons to the steady march of climate change — the potential scope of the agenda was vast. So it was significant that the leaders devoted part of the summit’s agenda and communiqué to the risks facing critical supply chains and the need for greater resilience.

Nowhere is this more concerning for the world economy than in the case of Taiwan. We are at a time of heightened tensions between the United States and China. An all-powerful President Xi Jinping is intent on reuniting the two rival Chinese republics. Consequently, the concentration of semiconductor manufacturing in Taiwan is the biggest geopolitical risk facing supply chains today.

Taiwan-based companies control more than 90% of the world’s production of advanced microchips. These chips are used in everything from high-end smartphones to cutting-edge military hardware. One company, Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Co. (TSMC), dominates this niche and owns more than half of global chip-making market share.

A Chinese invasion or blockade of its neighbor across the Taiwan Strait would have a devastating impact on the global economy — one far greater in scale and longevity than the havoc wrought on food and energy supplies by Vladimir Putin’s aggression last year. So it is right that G7 leaders focused on the issue.

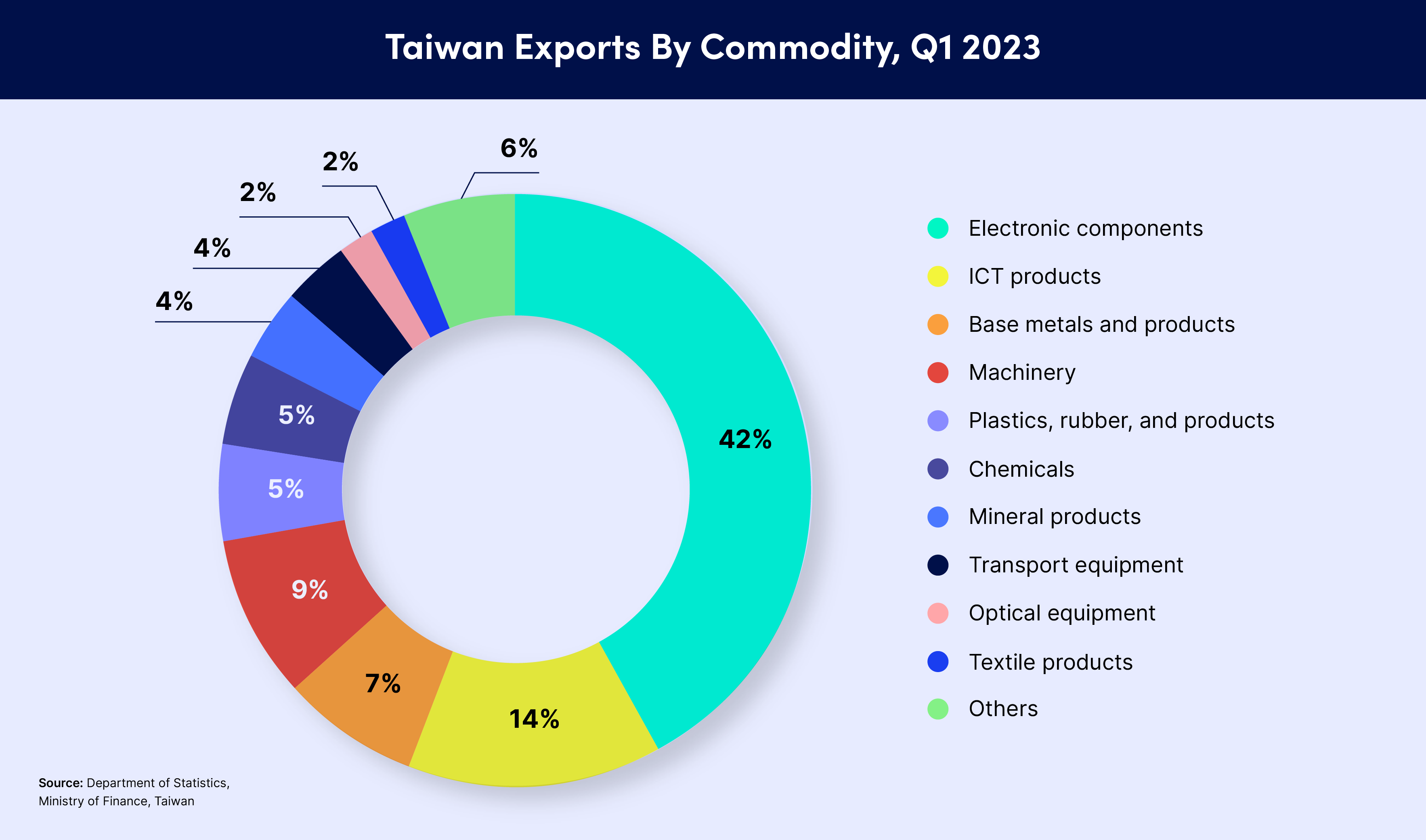

Taiwan’s Supply Chain: Powered by Semiconductor Exports

Taiwan exported $479.4 billion of products in 2022. The U.S. was the second biggest importer after China, with 15.7% ($74.9 billion) of the total. Japan was fourth with 7% behind Hong Kong, while the other five G7 countries — Canada, Germany, France, Italy and the U.K. — made up a combined 4.3% ($20.9 billion).

Many different products are shipped to these and other nations in Asia-Pacific and beyond (see chart). But it is electronic components, and especially “integrated circuits/microassemblies” — in other words, semiconductors — that dominate the list. The latter accounted for $183.5 billion, or 38% of Taiwan’s total exports by value last year. Despite a falloff in demand for chips in recent months, this figure was up 17.7% on 2021, which in turn was up 22.4% on 2020.

Dependence on Taiwanese supply chains among G7 countries is, as you might expect, extensive. An analysis of Interos’ global database of business relationships shows that:

- U.S. companies have almost 70,000 direct (tier-1) relationships with Taiwanese suppliers. Companies in other G7 member countries have almost 10,000 between them.

- When indirect multi-tier relationships are included, G7 member companies have more than 315,000 tier-2 and 750,000 tier-3 connections to Taiwanese firms.

- Although tier-1 relationships with the two major Taiwanese semiconductor manufacturers, TSMC and United Microelectronics Corp. (UMC), are relatively small in number (led by the U.S. with around 220), as tier-2 and tier-3 suppliers these two companies are present in hundreds of thousands of supply chains in G7 countries.

The Likelihood and Impact of China Invading Taiwan

Two key questions that arise from discussions around the China-Taiwan situation are:

- How likely is it that China will seek to take Taiwan by force, and when might this happen?

- What impact would Chinese action against Taiwan have on the global economy and supply chains?

Opinions among commentators and analysts on the first question vary widely. Some see an invasion occurring as soon as later in 2023, to sometime in the 2030s, to never. China’s official policy is one of peaceful reunification. However, U.S. intelligence reports suggest that President Xi has ordered the People’s Liberation Army to develop capabilities to seize the island by military force by 2027.

A geopolitical risk assessment of conflict between China and Taiwan by Interos concluded that the likelihood of an invasion in the next 2-5 years was “roughly even odds (45-55%).” The assessment also noted that “the majority consensus [among government policy makers and think-tank experts] appears to be that there will be an armed conflict over the island.”

On the second question, Interos’ analysis identified that a partial blockade or full invasion could disrupt ocean and air cargo shipments from Taiwan. Our analysis also raised the possibility that Taiwan could be completely cut off from international trade.

Potential Supply Chain Scenarios for Semiconductor Disruption

A tabletop exercise conducted last year among U.S. government and business leaders by the RAND Corporation centered specifically on the likely impact to advanced semiconductor supply chains. Participants were asked to consider two potential scenarios in which China imposed a “coercive quarantine on Taiwan”:

- Uncontested, China acquires a significant portion of global semiconductor capacity. This leaves the U.S. and other countries with a choice of continuing to buy from Taiwanese suppliers or imposing sanctions on China.

- China faces resistance in its attempts to take control of Taiwan’s fabs. This leads to a rapid loss of access to the country’s semiconductors, and triggers U.S. and other government action to ration limited supplies.

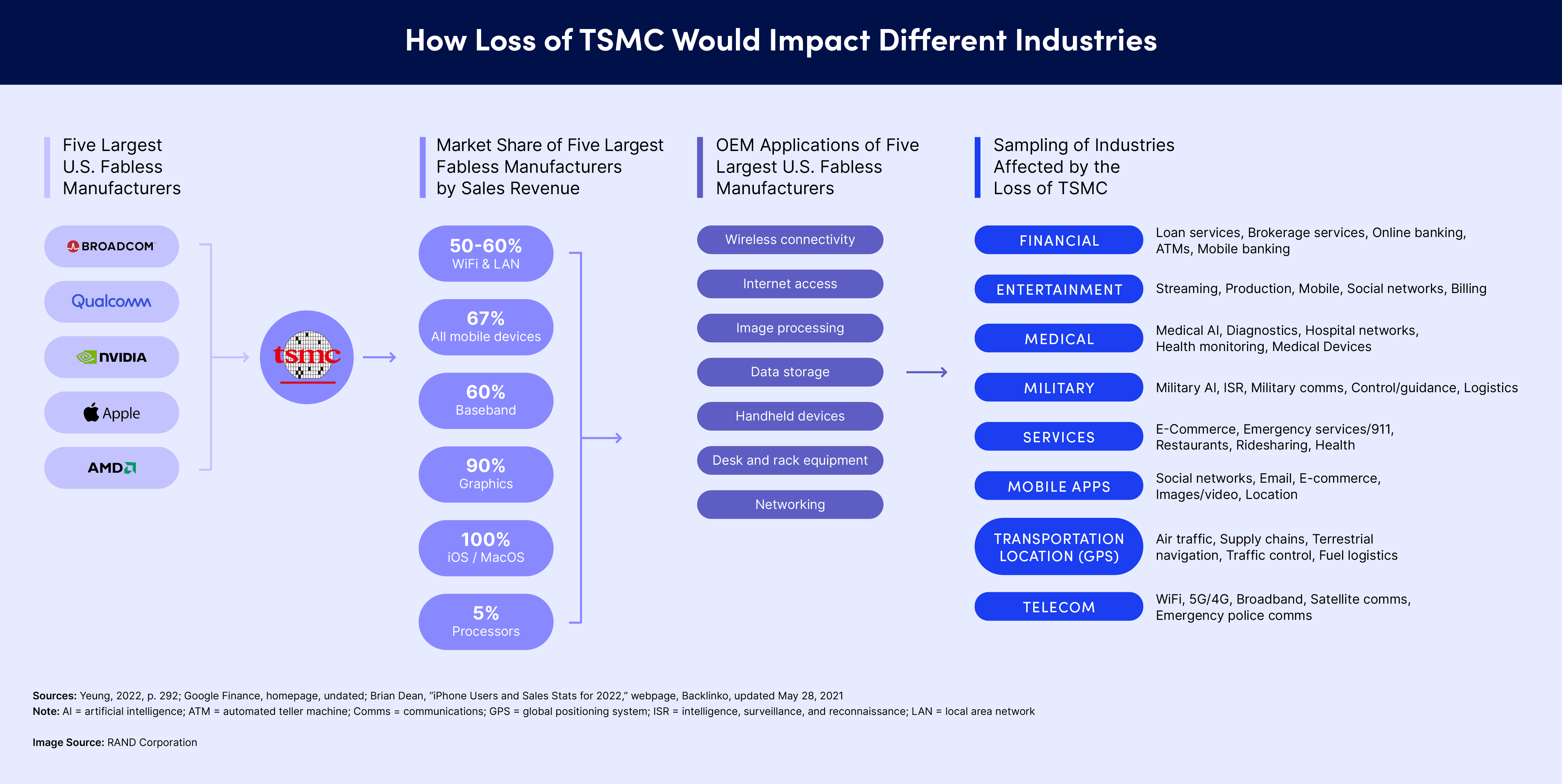

Unpalatable outcomes from these two scenarios included a fundamental change in the balance of global power in China’s favor, and an extended economic depression for most of the world. Unsurprisingly, given the impact on multiple industries (see graphic), business participants were keen on ensuring continuity of supply even if this meant relying on semiconductor firms such as TSMC under Chinese control.

Military action against China, whether by Taiwan or the U.S. and its allies, was not considered in this simulation. But a recent assessment by The Economist laid bare the imbalance in military capabilities between China and Taiwan. The analysis also articulated the dire consequences of military conflict over the island state. This included “incalculable damage to the world economy” as a result of disruption to semiconductor supply chains.

The threat of war looms large over the Indo-Pacific region. Hence efforts in recent weeks by Japan and other G7 countries, including the U.S., to take some of the heat out of relations with China. In their communiqué, the G7 leaders emphasized that actions designed to boost economic and supply chain resilience were about “de-risking, not de-coupling” from China.

Some Major Players Begin Diversifying Chip Capacity Away From Taiwan

In practice, de-risking means diversification. Since their 2022 meeting in Germany, the response of G7 countries to semiconductor concentration risk has been to tempt advanced chip-making capacity away from Taiwan through vast public subsidies. The U.S. has led the way with its CHIPS and Science Act, but Japan, the European Union, and the U.K. have all followed suit, albeit with fewer billions of dollars to throw at the problem.

Over the next five years these industrial policies should result in new fabs, supply chains, and skilled workforces being developed in multiple geographies. However, Taiwan is set on keeping much of its domestic semiconductor “shield” intact, both in terms of manufacturing and R&D. Aside from contributing 15% of Taiwan’s GDP, the industry serves as vital leverage for Taiwan in its efforts to maintain independence from China.

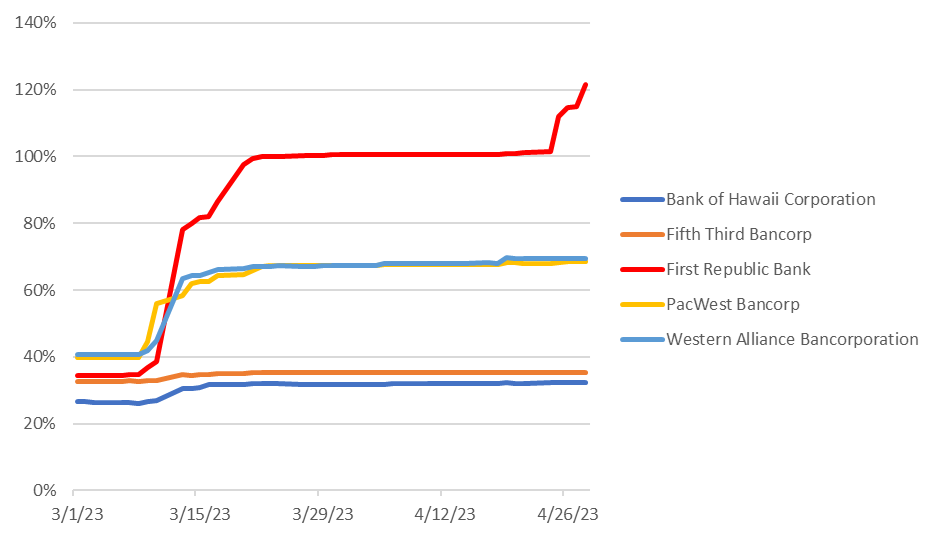

Confidence in this strategy in waning in some quarters. \Warren Buffett’s Berkshire Hathaway recently announced that it had sold the remainder of its $4.1 billion stake in TSMC. This is in spite of the fact that the shares were purchased as recently as November last year — and that TSMC is regarded as one of the world’s best-managed companies.

“I don’t like its location,” Buffett told analysts. “I feel better about the capital that we’ve got deployed in Japan than in Taiwan.”

Action CPOs Should Take to Prepare for Potential Disruption

To reduce the exposure of their organizations to semiconductor concentration risk, chief procurement officers should do the following:

- Assess your dependence on Taiwan by understanding the relationships you have with Taiwanese suppliers. Include both the direct, tier-1 relationships and those at tiers 2, 3 and beyond. Chip makers such as TSMC and UMC are often present at this sub-tier level.

- Evaluate the extent to which key semiconductors, electronic components, and other items you depend on from Taiwan-linked supply chains are single- or sole-sourced. Identify where you have viable alternative options already in place.

- Develop a strategy aimed at diversifying your supply base to other geographies. Consider sourcing from new suppliers and/or by working with existing partners to utilize alternate and emerging capacity.

- Conduct scenario plans and risk simulations – like the one run by British telecommunications group BT last year. These can gauge the impact that disruption to Taiwanese semiconductor supply chains might have on your business.

- Continuously monitor your Taiwan-dependent supply chains for geopolitical, operational, financial, and cyber risk events.

Until new semiconductor capacity comes online in the U.S., Japan, Germany, South Korea, and elsewhere, companies will continue to over-rely on Taiwan-based suppliers. However, it is important to be prepared for, and to support the creation of, a more diversified global supply chain for microchips – as it is with other critical products and raw materials that are heavily concentrated in particular geographic locations.