By Kate Anderson, Scott DeGeest and Teddy DeWitt

Amid the coverage of the evolving U.S. banking crisis that has claimed Silicon Valley Bank (SVB), Signature Bank, and First Republic Bank (FRB), and is now threatening PacWest, one aspect has remained largely hidden – the potentially massive supply chain impact of these failures.

Make no mistake, a banking crisis is also a supply chain crisis.

Interos data suggests that, thanks to the supply chain ripple effect, over 600,000 U.S. firms will be indirectly affected by the collapse of SVB and FRB alone.

Our research also indicates that, by considering banks as part of a larger supply chain and monitoring specific risk indicators, organizations – and especially their procurement leaders – can anticipate potential problems and banking failures well in advance.

So why are these banks failing? What does it mean for the broader supply chain? And what can organizations do about it?

The Banking Sector: A Supply Chain of Capital

As banks experience greater volatility, a tougher business environment and fleeing depositors, it becomes more difficult for them to obtain capital to distribute to their customers.

Much as supply chain disruptions limit access to vital goods, disruptions in the banking supply chain limit access to vital capital. This, in turn, impacts a whole range of day-to-day banking services that businesses rely on, including liquidity management, accounts payable services, lines of credit, foreign exchange services, and lending.

As with SVB, capital supply chain failures ultimately extend far beyond the financial sector and into the wider economy. Even companies not directly reliant on the bank’s capital were affected when they discovered that suppliers and service providers that banked with SVB were at risk. For example, users of Rippling – a major payroll platform – suddenly discovered that their operations were threatened by that supplier’s reliance on SVB.

Despite these impacts, companies seldom view financial crises through a supply chain risk lens. This is an oversight that, if corrected, could enable them to anticipate and prepare for these significant disruptions, rather than simply reacting after the event.

The importance of this kind of anticipation has become all too clear in the last few weeks and is likely to remain so given the prospect of additional volatility in the short to medium term – with regional bank stocks like PacWest continuing to slide.

So how can organizations use Interos’ data to understand the pinch in the capital supply chain that portended the collapse of FRB, for example?

Using Interos Supply Chain Data to Identify the Banking Capital Market Pinch

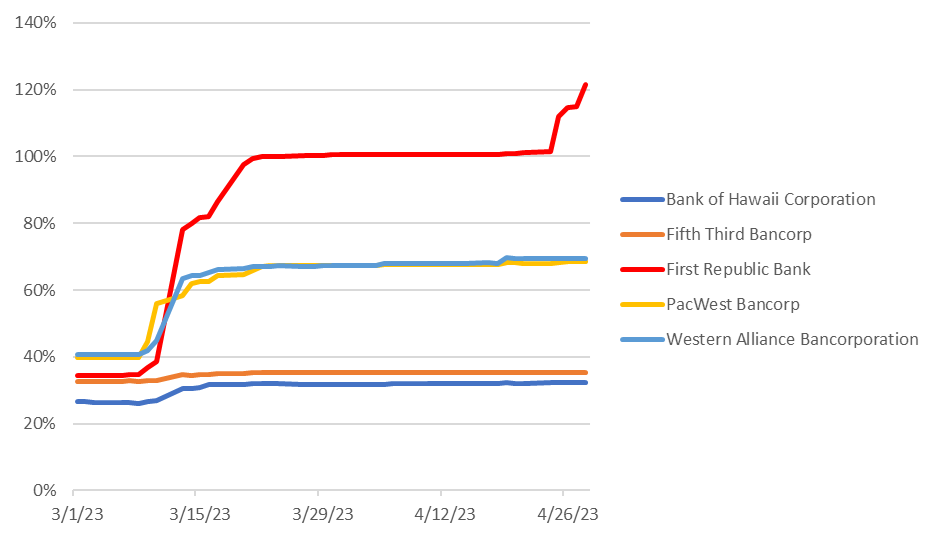

Volatility is a measure of how much a stock price moves over time. Increasing volatility indicates higher perceived risk, and can be an indicator that the overall risk, and potential vulnerability, of the business has increased.

Chart 1: Stock Volatility of Regional Banks

Source: Interos Analysis

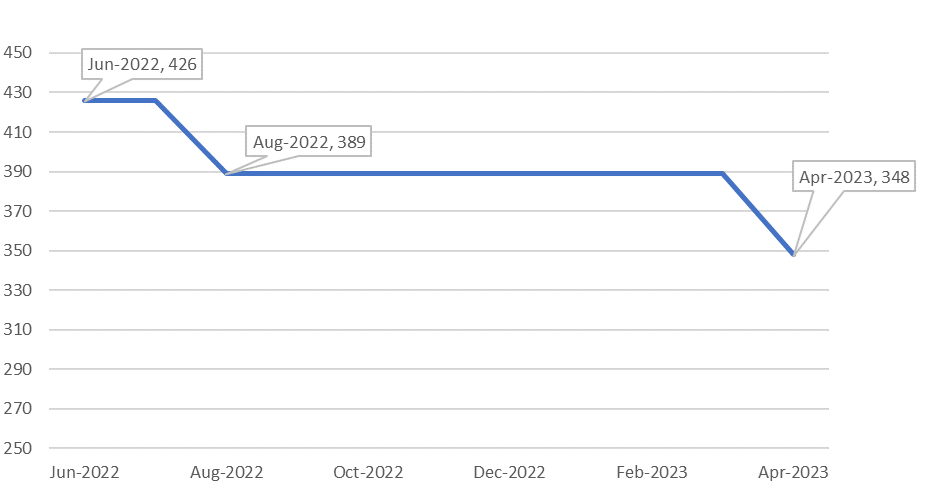

In addition, an analysis of metrics from the Interos platform showed FRB’s liquidity access steadily decreasing from June 2022, driven by an increase in its use of non-financial trades (see chart 2).

Chart 2: Liquidity Access Score for First Republic Bank

Source: Interos Analysis

Identifying the Ripple Effects on the Wider Supply Chain

Capital constraints ripple through the broader supply chain ecosystem, as was evident during the collapse of SVB, and now FRB.

Interos’ resilience platform documents 3,000 direct (tier-1) business relationships for SVB and FRB. But it also shows almost 600,000 indirect (tier-2) connections. These are companies that don’t bank directly with SVB or FRB but have a supplier that does.

For example, suppose Acme Corp. banks with SVB and provides IT services to Bravo, Inc. A failure in SVB would potentially disrupt payroll for Acme Corp., which might limit the services that Acme can provide to Bravo.

Without visibility into its extended supply chain, Bravo would be unable to anticipate the ripple effects of this failure.

Once a firm at the center of a capital supply chain disruption has been identified, the Interos platform enables procurement professionals to identify which tier-1 and tier-2 suppliers rely on that firm for vital goods and services.

How Organizations Should Respond to Potential Bank Failures

To respond to a capital supply chain disruption and get ahead of future problems, procurement organizations should do the following:

- Identify essential tier-1 and tier-2 suppliers that use regional banks.

- Coordinate contingency plans with these suppliers to address liquidity crunch issues and concerns about inventory management in the event that their banking partners experience a credit pinch.

- Review the recent credit history of capital suppliers (regional banks) to look for signals of distress such as increases in non-financial trades.

- Monitor the financial situation of your own banking partner(s) for any declines in access to liquidity.

Network effects, high volatility, and liquidity crunch issues will continue to be a problem for regional banks – with PacWest just the latest example – in the near term.

Owing to their smaller and often more concentrated deposit bases, regional banks are more susceptible to supply chain disruption from capital flight.

Interos’ approach to this type of risk, as described here, integrates financial data with supply chain network data and news alerts to flag potential problems in advance and provide guidance on navigating the aftermath of a crisis.