By Michael Eddi & Harris Allgeier

Global supply chains continue to feel the string of an escalating trade war as China implements a new range of export restrictions targeting yet another important raw material: Graphite. The latest in a series of export controls levied by China, in a tit-for-tat battle of trade restrictions with the US, these new controls have significant ramifications for a swathe of industries including Aerospace & Defense, electric vehicles, and manufacturing.

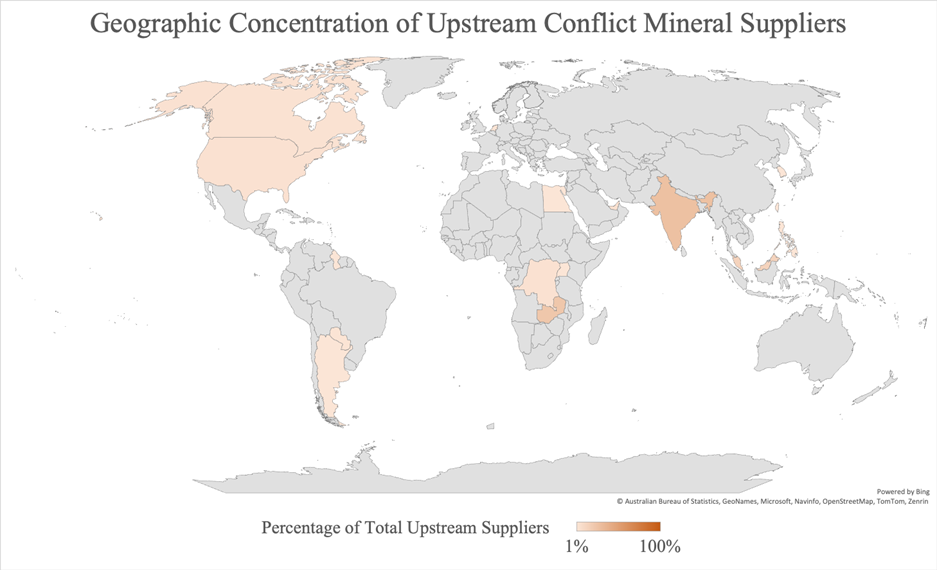

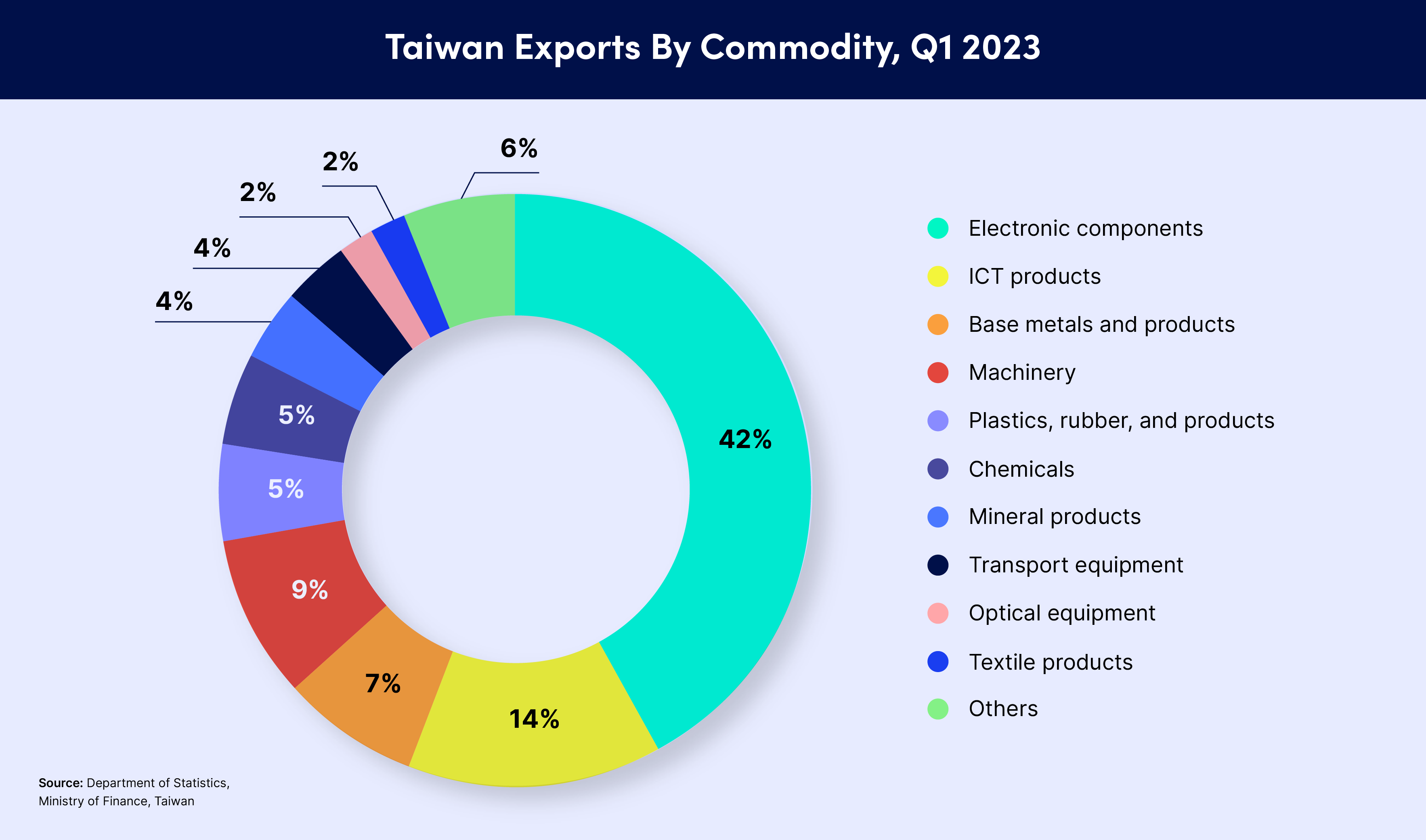

In 2021, China produced 79.1 percent of the world’s natural graphite, despite only having 22 percent of global reserves. The new laws require export permits for two types of graphite, including high-purity, high-hardness synthetic graphite, and natural flake graphite and its products. These controls took effect December 1, 2023. (Click here to read a full translation of the new regulations)

The move comes on the heels of similar Gallium and Germanium export controls, levied by China in 2023. China’s Ministry of Commerce (MOC) has classified all these materials as dual-use items under export control. “Dual use” in this context means materials that have potential military and civilian applications.

Interos analysts looked at the possible impacts these new regulations could have for the electric vehicle and A&D sectors. We then created guidance for what supply chain leaders can do in response.

1. Graphite Restrictions’ Impact on Electric Vehicle Affordability

China produces nearly 100 percent of the processed graphite used to create battery anodes used in electric vehicles. The US is taking initial steps to help diversify graphite production. However the US currently has no domestic production of natural graphite and no domestic processing of graphite into anode materials for EV batteries. A potential graphite scarcity will reverberate through the entire production process, leading to higher overall production costs for EV manufacturers. This could impact the affordability of electric vehicles, reducing the adoption of clean energy transportation globally at a time when demand has already leveled off.

Furthermore, export controls on graphite from China could instigate a broader reassessment of supply chain strategies within the EV industry. EV firms might be compelled to diversify supply sources for critical materials, including graphite, to mitigate risks associated with sole-source dependency.

This strategic shift could involve exploring alternative global suppliers or fostering the development of domestic sources, to create a more resilient and distributed supply chain.

In South Korea, EV and battery manufacturers have been focusing on silicon anode materials as a key strategy to reduce dependence on Chinese graphite. This next-generation material is estimated to have “[…] an energy density about 10 times higher than the graphite-based anode materials currently used in most electric vehicle batteries But it will be years before these materials can meaningfully replace Chinese graphite on a global scale.

The US is also investing in alternate graphite sources, with the Department of Defense awarding a $37.5 million contract to Canadian company Graphite One.

2. Graphite Restrictions’ Impact on Aerospace & Defense Operational Readiness

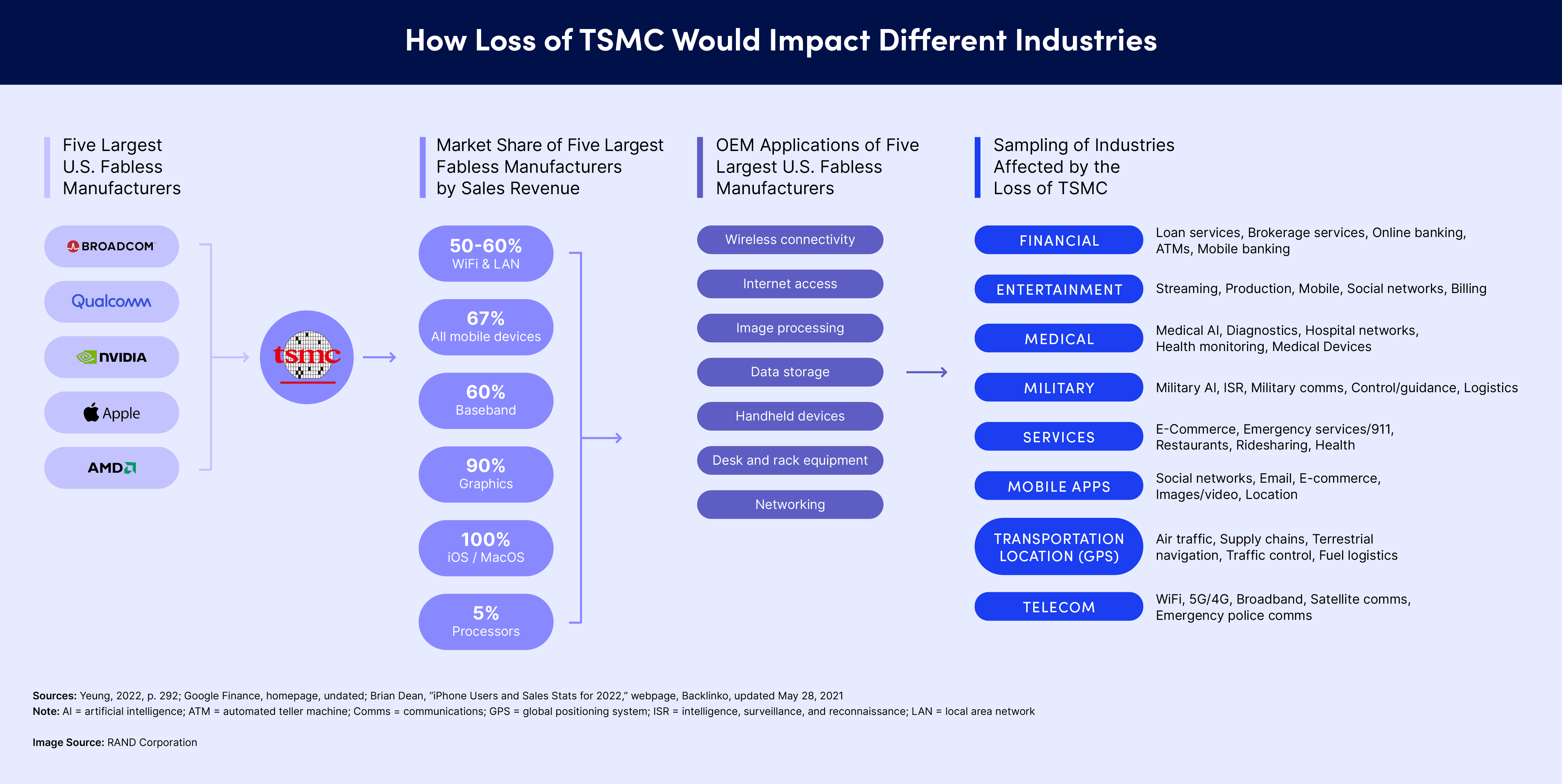

Graphite is used in a wide variety of various military applications in the A&D sector, including missile systems, jet components, body armor, and electronic components. Export controls on graphite could impact the operational readiness and capabilities of multiple defense systems. The strategic repercussions of this are even more severe during these times of heightened international tension, which inherently call for increased preparedness for conflict.

Domestically, the United States has looked to shore up its graphite extraction, refinement, and production capabilities via private entities. However these are a long way away from matching the levels currently imported from China.

3. An Increasingly Restricted Supply Chain

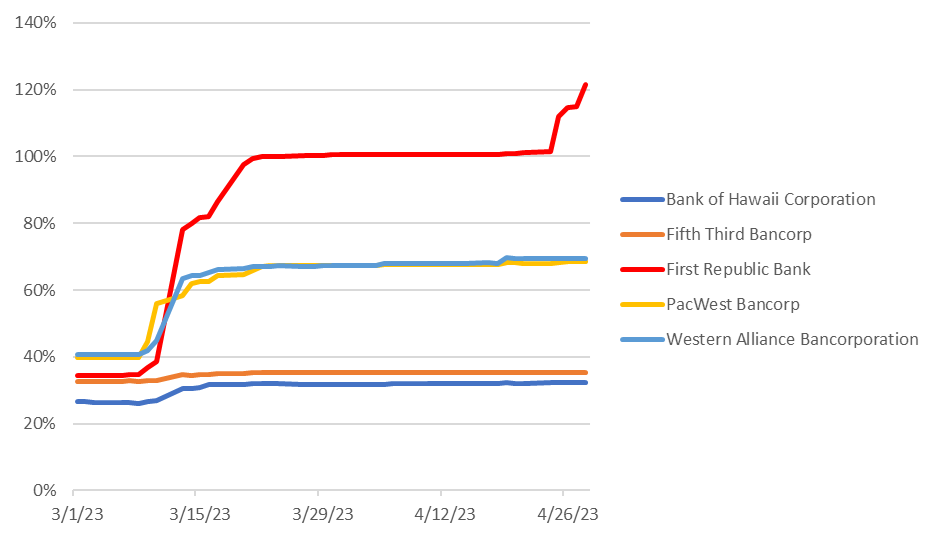

China’s new regulations will ensure a stable supply of graphite for its growing domestic industries. They will also offer the country greater economic control over other nations dependent on Chinese graphite. However, the decision to restrict graphite exports is considered by many as a retaliatory move, influenced by the US’s recent restrictions on exporting high-tech AI chips to China. The restrictions also come on the heels of several recent efforts by the Chinese government to limit access to critical raw materials used in semiconductors and advanced technologies.

China isn’t the only country to take a more protectionist stance on natural resources. Resource nationalization is sweeping across the Asia-Pacific region. In recent years Malaysia, Indonesia, Mongolia, India, and other countries have all implemented (or announced the intent to implement) legislation to secure critical raw materials (usually rare earth elements) for domestic industries and reduce dependency on external suppliers.

China’s restrictions are likely driven by multiple factors. These include a growing domestic need for the material, the regional/global push towards nationalization, and the US’ recent restrictions targeting China.

The restrictions are a perfect example of a growing nationalization movement, where nations increasingly view control over critical resources as essential for maintaining economic resilience and national security. Overall, these trends underscore the complex interplay between economic interests, geopolitical strategies, and the evolving dynamics of global trade. All of these play a crucial role when considering how to build a resilient supply chain.

4. What can supply chain leaders do?

Supply chain managers in aerospace & defense, the electric vehicle sector, and other industries impacted by the new graphite export controls, or other recent trade restrictions, have several strategies available to them.

- Advanced Intelligence and Continuous Monitoring: Utilize leading vs lagging risk indicators to continuously monitor potentially impacted suppliers and identify any vulnerable portions of your supply chain. The Interos platform tracks 400M+ entities in real-time to pre-empt sub-tier risk for aerospace and defense, technology, and other sectors.

- Diversify Sourcing: Screen for alternative sourcing options for graphite from countries or regions not subject to import controls. Diversifying suppliers can help reduce the reliance on a single source and minimize the disruptions caused by import controls. This is also known as the process of identifying potential alternative suppliers that may exist within your industry’s periphery.

- Optimize Your Supply Chain: Review and optimize your supply chain to identify potential bottlenecks and vulnerabilities caused by export controls. Streamlining processes, improving logistics, and establishing backup plans can help ensure a smoother flow of materials despite regulatory constraints.

- Maintain Regulatory Compliance: Stay updated on fast-moving export regulations and ensure full compliance with the requirements. Engage in advocacy efforts and lobbying activities to influence policymakers and advocate for more favorable import control policies that align with the interests of your supply chain.

- Identify New Strategic Partnerships: Forge strategic partnerships with suppliers, distributors, and industry associations to collectively address challenges posed by import controls. Collaborative efforts can help leverage collective bargaining power and facilitate the sharing of resources and expertise.

To learn more about how Interos can help you manage regulatory compliance and identify latent geopolitical risk within your supply chain, click here.