By Geraint John

Satellites are becoming the new supply chain battleground in critical infrastructure as countries seek to bolster their military capabilities and national security against the threat of war.

However, this is not some James Bond-style plot in which rival powers vie for control of space-based nuclear weapons, as in the 1995 film GoldenEye, but something more prosaic: a quest for bomb-proof internet connectivity.

Ukraine’s success in stemming the Russian army’s advances across its territory have been credited, at least in part, to its access to Starlink, a constellation of more than 3,000 low-orbit satellites owned and operated by Elon Musk’s company, SpaceX.

Ukraine’s military relies on Starlink’s fast, reliable internet access to share battle plans, co-ordinate operations and target Russian positions.

In the words of a Ukrainian soldier quoted in a recent Economist article: “Starlink is our oxygen.” Without it, “our army would collapse into chaos”.

The Satellite Supply Chain: Low Orbit, High Potential

Other nations concerned about their vulnerability to attack and the security of their land- and seafloor-based fiber-optic cables for internet traffic, are keeping close tabs on Ukraine’s experience.

Taiwan, which has seen tensions with China escalate during the past year, is reported to be seeking private investment to establish its own satellite communications network.

China itself has submitted plans for a 13,000-satellite constellation, Russia has designs on a 264-satellite network, while the European Union agreed late last year to begin developing its own low-orbit system.

Japan, South Korea and Australia are among other countries looking to operate similar constellations of their own in the future.

Unlike traditional geostationary Earth orbit (GEO) communication satellites, which fly more than 35,000km above the planet’s surface, low-Earth orbit (LEO) satellites operate much closer to home.

Starlink’s satellites orbit just 550km from Earth, which means they can receive and transmit data much faster, making high-bandwidth internet streaming and video services possible.

Other benefits include the fact that:

- They communicate with users on the ground via portable and easily powered receiving equipment

- Their (stronger) signals are harder to jam

- Russian efforts to hack them have so far been ineffective

- Because there are hundreds of satellites serving each location, physically taking the network down – through, say, a missile attack – would require enormous scale and vast expense.

America’s World Domination May Lead to Imbalanced Supply Chains

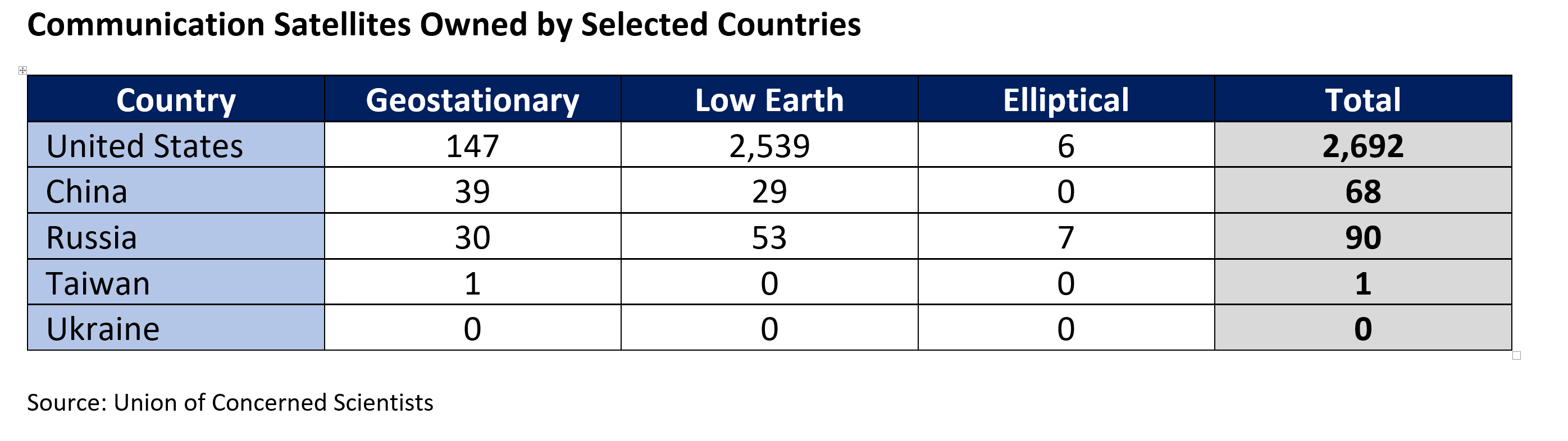

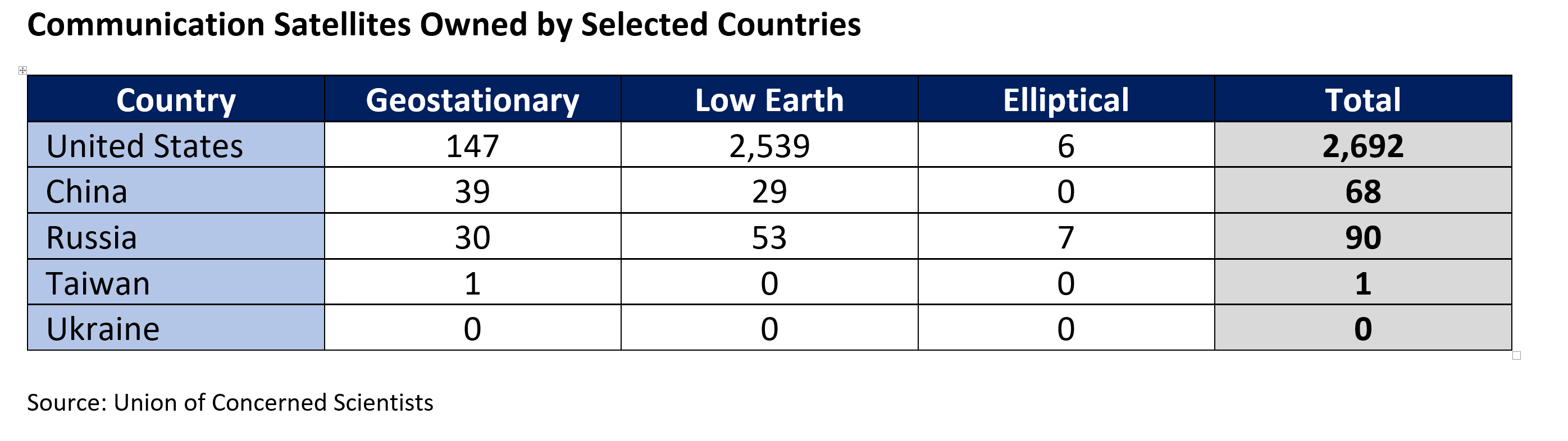

The United States dominates global satellite ownership, with 63% of the almost 5,500 commercial, military, civil and government satellites launched to date, according to data compiled by the Union of Concerned Scientists (UCS), a U.S.-based nonprofit organization.

Its dominance in LEO satellites – which comprise 86% of the total satellite population – is even more pronounced, thanks to Starlink.

The U.S. owns almost 50 times as many LEO communication satellites as Russia, and almost 90 times more than China, according to UCS.

Building on this data, Interos has created a satellite concentration and diversification metric. The metric demonstrates the resilience the U.S. has in this area, with extremely high satellite diversification, whereas Russia and China are both rated a high concentration risk.

This is good news for supply chains in the U.S., but those in less diversified areas may increasingly be more prone to internet disruptions or complete blackouts.

Taiwan has just one GEO communications satellite, through a joint venture with Singapore’s telecoms provider, while Ukraine doesn’t own any and relies on those of its allies.

While Considering Future Satellite Trends, Beware Single Sources in Space

Aside from the potential for cyber interference in this newly critical and rapidly expanding infrastructure, from a supply chain perspective the main risk is arguably the extreme concentration of suppliers.

At present, Starlink is a de facto monopoly for customers outside of China and Russia, because of its dominance of launch capacity. Its Falcon 9 rockets took off more than 60 times last year and each is capable of carrying over 50 LEO satellites.

Rivals Blue Origin, owned by Jeff Bezos, the United Launch Alliance – a joint venture between Boeing and Lockheed Martin – and France’s Arianespace are all in the process of readying new rockets.

UK-based OneWeb – which partners with France’s Eutelsat and Airbus – is currently dependent on SpaceX after its access to Russian launch facilities was scuppered last year. And Virgin Orbit last month failed in its inaugural attempt to launch nine LEO satellites from British soil using a rocket mounted below a reconfigured 747.

Interos has implemented a new satellite concentration risk score, which evaluates the concentration of accessible communication satellites in a country. A country with more satellites or increased access receives a high score and has less risk of satellite disruptions. This score currently shows France as being very high risk – even higher than Russia and China – whereas the UK is medium risk. However, diversification should be an important objective for these and other countries over the next few years.

While industry analysts expect there to be four or five active competitors in this global market eventually, for now SpaceX can call the shots.

For example, although it abandoned a suggestion in October that it would start charging Ukraine for its services, it has restricted use of its network in Russian-occupied territory such as Crimea, according to The Economist.

Government, military and commercial procurement chiefs would therefore be wise not to put all of their bets in this new space race on Mr. Musk’s satellite network, which may well become the next frontier in supply chain concentration risk.