On the surface, the recent spyware campaign by the Vietnamese government against U.S. politicians may not seem relevant to supply chain risk. That would be a faulty assumption. More than 70 governments have deployed spyware over the last decade. While government officials and journalists are often the targets, the private sector is not immune. Businesses located in countries with governments deploying spyware and pursuing digital authoritarianism – widespread data and internet control – face a heightened risk of data exfiltration.

But spyware doesn’t just create cybersecurity risks, it also creates regulatory risk. Earlier this year, the Biden Administration introduced new restrictions on spyware companies due to the security risks they pose. Along with the UFLPA, these additions reflect a growing focus on human rights violators. These changes acknowledge “the increasingly key role that surveillance technology plays in enabling campaigns of repression and other human rights violations.”

In the new normal defined by geopolitical fault lines and a splintering of cyber norms, both the deployment and production of spyware should be a growing consideration for supplier due diligence and risk assessments.

The Proliferation of Spyware

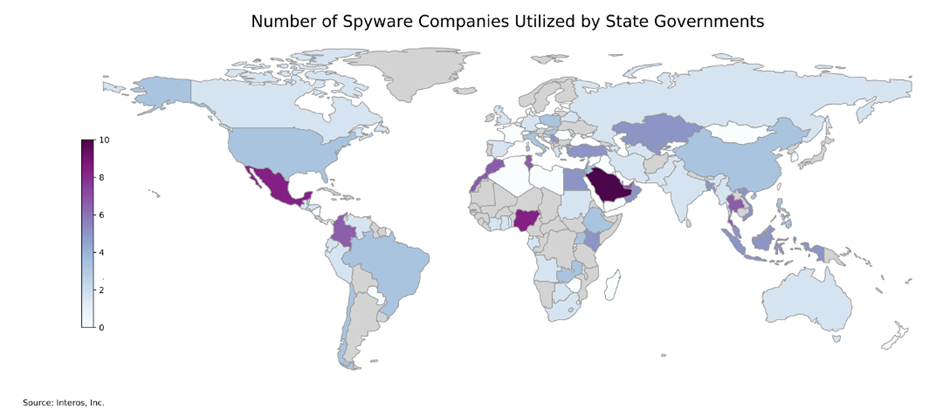

Spyware is a form of malicious software installed on devices to collect information without the owner’s consent. Previously, governments had a near monopoly on these capabilities. However, thanks to the privatization of spyware, offensive cyber capabilities continue to proliferate among state and non-state actors. NSO Group, Cellebrite, and Candiru are just a few of the companies selling spyware. A recent Interos analysis assessed the number of spyware companies linked to national governments. The number reached into the double digits in some cases.

These numbers only reflect the open source disclosure of spyware. In reality dozens of governments now possess some level of offensive cyber capabilities, the majority of which remain classified. China leverages spyware for widespread espionage campaigns, while reporting has linked numerous governments to Pegasus spyware. This year’s ODNI (Office of the Director of National Intelligence) Annual Threat Assessment notes “commercial spyware and surveillance technology, probably will continue to threaten U.S. interests.” ODNI estimates the commercial spyware industry to be worth $12 billion. Vietnam’s targeted deployment of spyware reflects this growing risk.

Spyware and Restrictions

The proliferation of commercial spyware and surveillance technologies is not only a security risk. It is also reshaping the regulatory environment. Section 889 of the 2019 NDAA was among the most expansive prohibitions against the use of surveillance technologies by federal agencies and their partners. Focused on Huawei, Dahua, ZTE, Hytera, and Hikvision, and their subsidiaries, Section 889 reflects the growing risks of surveillance technologies due to both data exfiltration risks as well as regulatory risks.

While Section 889 focuses on dual use surveillance technologies, this year’s Executive Order explicitly addresses commercial spyware focused on surveillance and data exfiltration. It has already resulted in several more companies being flagged as surveillance risks. This includes the addition of Intellexa and Cytrox to the Entity List. Initially, restrictions such as Section 889 largely focused on companies partnering with the United States governments. However this has been extended to a broader commercial restriction following the inclusion on the Entity list. This is not only a U.S. concern; the E.U. has called for a ‘de facto’ moratorium on spyware in May, while Australia has similarly debated controls on commercial spyware.

Looking Ahead: The Splinternet & Supply Chain Risks

Just as globalization and supply chains continue to be upended along geopolitical fault lines, so too does the internet. Reflecting opposing norms toward digital government intervention and data privacy, today’s siloed and fractured “Splinternet” introduces new digital risks across a company’s supply chain. Digital authoritarianism, wherein governments seek digital sovereignty and control over the Internet and the data passing through it, is on the rise and is powering the proliferation of spyware. While democracies are not immune from the use of spyware for national security, authoritarians are much less constrained on their use of offensive cyber capabilities across a growing population of targets.

The ODNI Annual Threat Assessment summarizes the national and commercial risks posed by digital authoritarianism and offensive cyber capabilities. Revelations of Vietnam’s use of spyware is not surprising to those following the expansion of digital authoritarianism. Over the last few years, Vietnam has adopted increasingly stringent data restrictions, including mandating local data storage and government control over data. These laws have prompted comparisons to Chinese digital authoritarianism and the data trap which eliminates corporations control over their own data.

Vietnam also is a top contender for companies seeking to diversify supply chains away from China. While it may provide favorable labor and economic environments, Vietnam’s cyber risks are often overlooked. While governments are more-frequently targeted than corporations by spyware, history has proven that it’s only a matter of time before business are equally under fire by adversaries with espionage or profit motivations.

Diversification with Cybersecurity and Regulatory Risk in Mind

As companies explore reshoring and supply chain diversification, the cybersecurity risk environment must be part of the calculation. A growing component of this analysis is the offensive deployment of spyware for data exfiltration. Similarly, surveillance technologies within a supply chain are also at heightened risk of regulatory fines and penalties. These heightened risks reflect ongoing geopolitical and technological transformations and introduce a range of opportunities and risks.

Those who prioritize and design operational resilience in sync with these transformations will gain a competitive advantage and be better prepared for the new normal compared to those who remain focused on the risks of yesteryear.

To learn more about how to identify and combat risks related to spyware in your supply chain, contact Interos.