The Millennium Falcon might look like a piece of junk but it can do point five past lightspeed and

– as they say in the bars of Tatooine – it’s got it where it counts.

Not bad for a bucket of bolts won in a card game.

In celebration of May the Fourth, Interos turned its artificial intelligence-powered supply chain

risk management technology on the company that makes the ship that made the Kessel Run in

less than 12 parsecs.

Our report is based on a detailed analysis of Star Wars lore with all companies mentioned

appearing in canon, the official collection of stories and history that Lucasfilm accepts as part of

the Star Wars saga. Our analysts dove deep into the available data, conducting a legitimate

analysis using the Interos platform.

What we found is a supply chain littered with risks as the Falcon operates in a universe with just a little bit of political instability, making it more than difficult to ensure the procurement of the

right part at the right time. This may go without saying, but it turns out an intergalactic war

fought between all-powerful space-wizards is bad for the widespread availability of necessary

parts and raw materials.

Let’s dive into our insights. Please note that none of our analysts died to bring you this

information, but there were algorithms and machine learning involved.

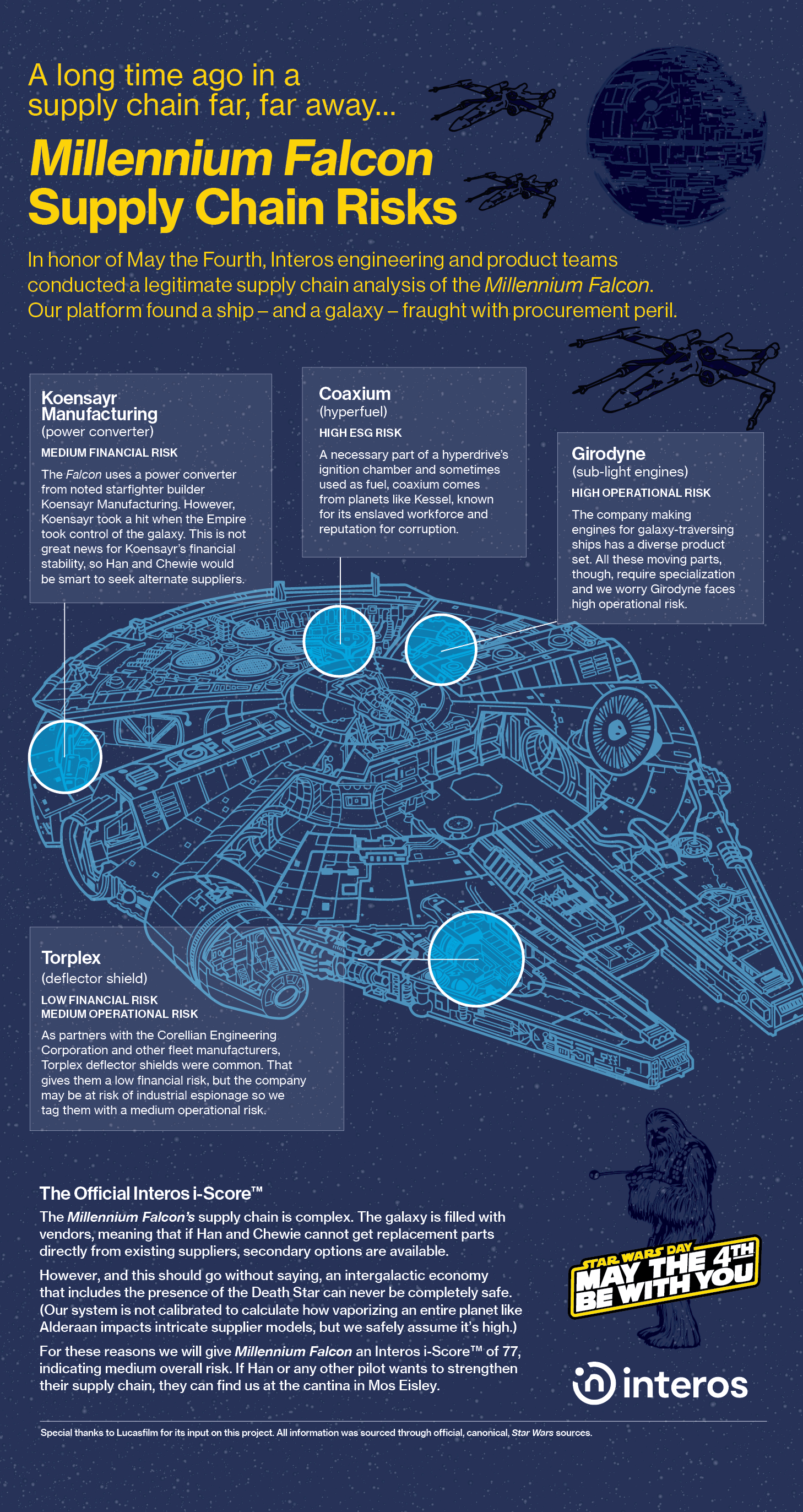

1. Koensayr Manufacturing (power converter): Medium Financial Risk

The Falcon uses a power converter from Koensayr Manufacturing, perhaps one of the top

makers of starfighters in the galaxy. However, Koensayr took a hit when the Empire took control

of the galaxy, losing out on several government contracts it held with the Galactic Republic. This

is not great news for Koensayr’s financial stability, so Han and Chewie may want to keep an ear

open for a new power converter supplier, just in case.

2. Torplex (deflector shield): Low Financial Risk | Medium Operational Risk

As partners with the Corellian Engineering Corporation (CEC) and later Sienar-Jaemus Fleet

Systems, Torplex deflector shields were quite common in a galaxy rife with competitors. That

gives them a low financial risk, but the company may find itself at risk for espionage with other

players in their field, so we tag them with a medium operational risk.

3. Coaxium (hyperfuel): High ESG Risk | High Operational Risk

A necessary part of a hyperdrive’s ignition chamber and sometimes used as fuel, coaxium

comes from planets like Kessel, known for its enslaved workforce and reputation for corruption.

After its rise, the Empire began to attempt to monopolize production of the substance as well.

4. Girodyne (sub-light engines): High Operational Risk

The company that makes engines for starfighters and other galaxy-traversing ships has a fairly

diverse product set. All these moving parts, though, require specialization and we worry

Girodyne finds itself at a high operational risk, since it leans so heavily on its own suppliers for

success.

5. Phylon Transport (tractor beam): Low Political Risk | Low Financial Risk

The maker of the Falcon’s tractor beam emitter found itself in a good spot, thanks to

relationships with CEC and the Kuat Drive Yards, two major ship producers.

6. Cloud City (gas mining colony): High Political Risk

The Falcon likely used tibanna gas to cool its hyperdrive, which would be abundantly available

in Cloud City. Sadly, Han and Chewie’s last trip there ended… poorly. Cloud City remains on

many intergalactic restrictions lists as of this writing, so the Corellian Engineering Corporation

may want to look for suppliers elsewhere.

The Official Interos i-Score™

The Millennium Falcon’s supply chain certainly has its challenges. The galaxy is filled with

spaceships and spaceship parts, meaning that if Han and Chewie cannot get a replacement

part directly from a supplier, there are certainly secondary options available.

However, and this should go without saying, an intergalactic economy that includes the

presence of the Death Star can never be completely safe. (Our system is not calibrated to

calculate how vaporizing an entire planet like Alderaan impacts intricate supplier models, but we

safely assume it’s high.)

For these reasons, we will give the Corellian Engineering Corporation, makers of the Millennium Falcon, an Interos i-Score™ of 77, indicating medium overall risk. If Han or any other pilot is

worried about their ship’s supply chain and ever wants to improve their operational resiliency, they

can find us at the cantina in Mos Eisley.

Special thanks to Lucasfilm for its input on this project. All information was sourced through

official, canonical, Star Wars sources.