By Geraint John

Since the U.S.-China trade war kicked off in early 2018, “supply chain resilience” has become a top agenda item for procurement leaders, company bosses and legislators alike.

The case for resilience has been massively strengthened during this period by the COVID-19 pandemic, severe semiconductor shortages, and most recently Russia’s invasion of Ukraine.

But what started out as a largely operational effort by businesses to shore up fragile supply chains is in danger of being subsumed by political considerations, as governments pour money into favored firms on home soil in an attempt to reverse globalization.

In this febrile atmosphere, advocates of operational resilience need to guard against attempts to narrow its focus unduly to national interests and protectionist trade policies.

Globalization & bringing production ‘back home’

Recent years have seen a growing debate about whether globalization — a 30-year-plus stretch in which hundreds of thousands of firms shifted production to far-flung destinations in search of cost efficiencies — is in retreat.

Bringing sourcing and manufacturing activity back to home countries (onshoring or reshoring) or neighboring ones (nearshoring) is seen as proof that global supply chains are not the panacea they once were.

After several false starts, in which there has been plenty of talk but relatively little action, Wall Street is now pointing to evidence that suggests a reverse trend may finally be real.

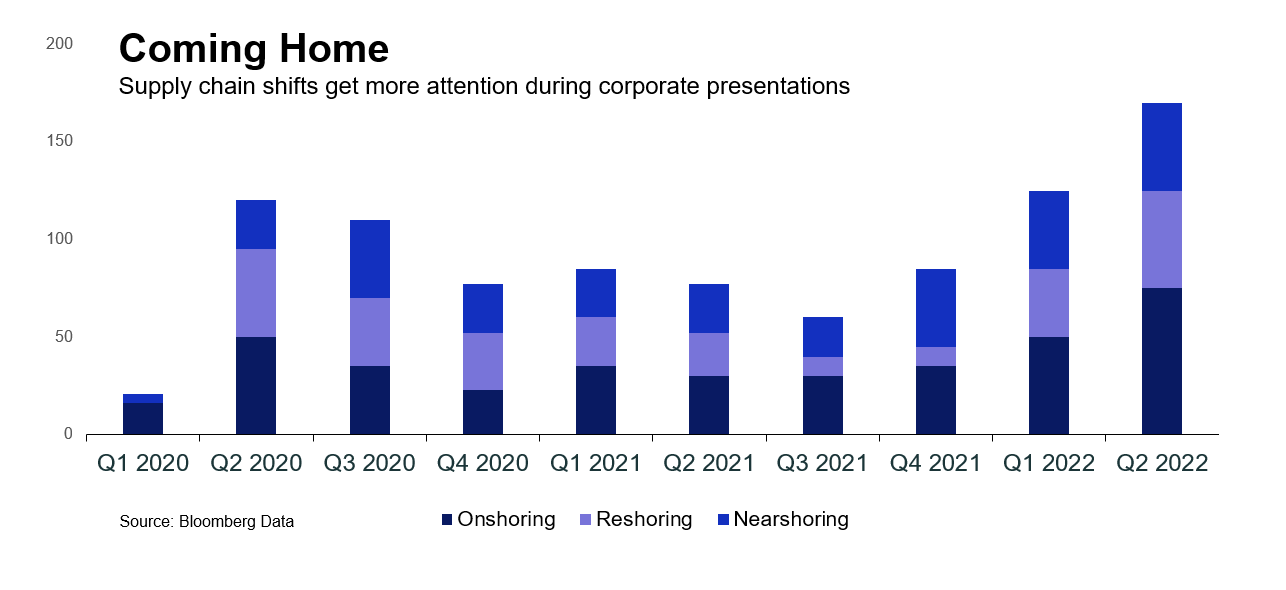

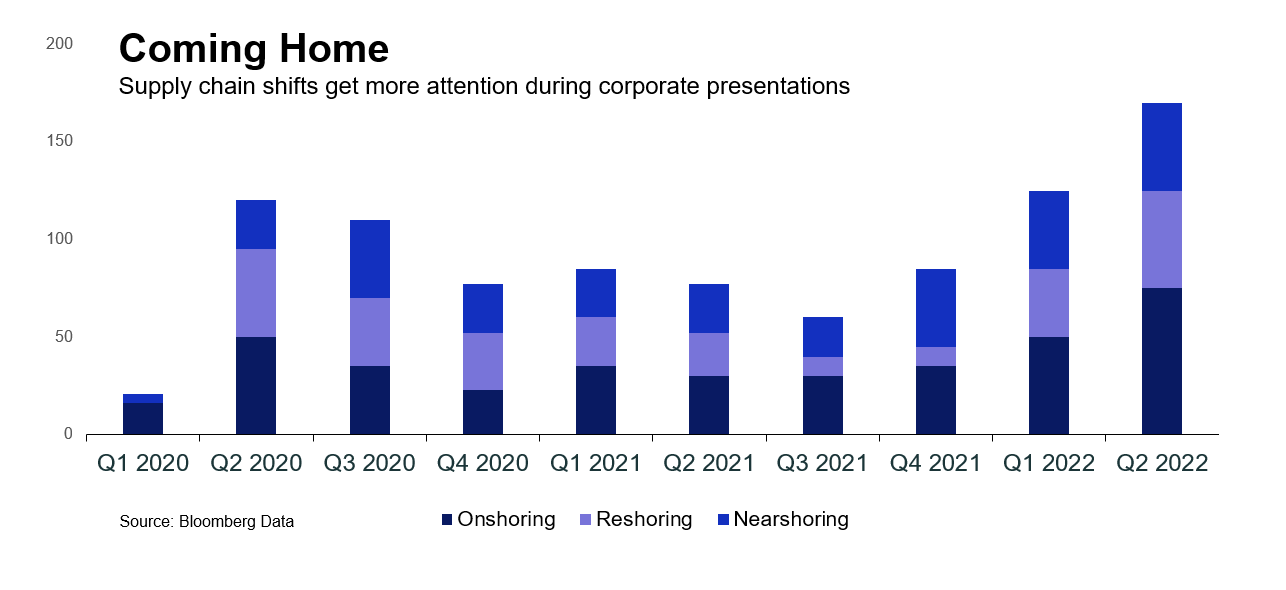

Last month, analysts at Bank of America and Barclays were among those who noted a growing number of references to reshoring by CEOs and other senior executives at S&P 500 companies during second-quarter earnings calls.

Data from Bloomberg shows a 1,000% increase in use of the terms onshoring, reshoring, and nearshoring in these calls compared with pre-pandemic levels (see chart).

The business drivers for changing global operating models in this way include:

- A closing of wage differentials between offshored locations — especially China — and home nations

- More expensive logistics costs to transport components and finished goods by air and sea

- Extended lead times and shortages of materials and labor caused by COVID lockdowns and other disruptive events

- The need to respond more quickly to evolving customer requirements in local markets

An expanding national security agenda impacts operational resilience

At the same time, governments in the U.S., Europe and elsewhere are pushing for the rebuilding of domestic supply chains in the name of national security and self-sufficiency.

In practice, this means reducing dependence on China and Russia as tensions escalate and a largely stable and benign era of international free trade is fractured by the battle for global economic and geopolitical supremacy.

Russia’s war in Ukraine highlighted just how reliant many countries are on it for supplies of oil and natural gas, as well as many critical industrial and agricultural commodities.

China, meanwhile, remains the world’s preeminent manufacturing base, and an electronics powerhouse that dominates supply chains for everything from 5G networks to lithium-ion batteries.

Both countries have been subjected to an ever-growing list of Western sanctions and export controls, with Russia essentially closed for business and China’s access to U.S. and European chip-making equipment and related technologies heavily restricted.

U.S. House Speaker Nancy Pelosi’s controversial visit to Taiwan at the beginning of August shone a spotlight on that island’s almost total control of advanced semiconductors — used not only in the latest smartphones, but also cutting-edge military systems — and its vulnerability to a Chinese takeover.

A&D semiconductor supply chains rely on Taiwan and China

An analysis of Interos’ global relationship platform data shows that:

- The major U.S. aerospace & defense (A&D) companies each have as many as 85 direct (tier-1) relationships with semiconductor suppliers

- The vast majority of these tier-1 relationships are with U.S.-headquartered companies, led by the likes of Intel, Broadcom and Nvidia

- At the tier-2 level, big Taiwanese chip makers such as Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Co. (TSMC), Advanced Semiconductor Engineering (ASE) and United Microelectronics Corporation (UMC) have hundreds of connections to U.S. A&D supply chains

- SMIC, China’s largest semiconductor manufacturer, has over 300 connections to tier-1 suppliers serving U.S. A&D customers, and there are many other Chinese-owned suppliers present in these supply chains at tiers 2 and 3

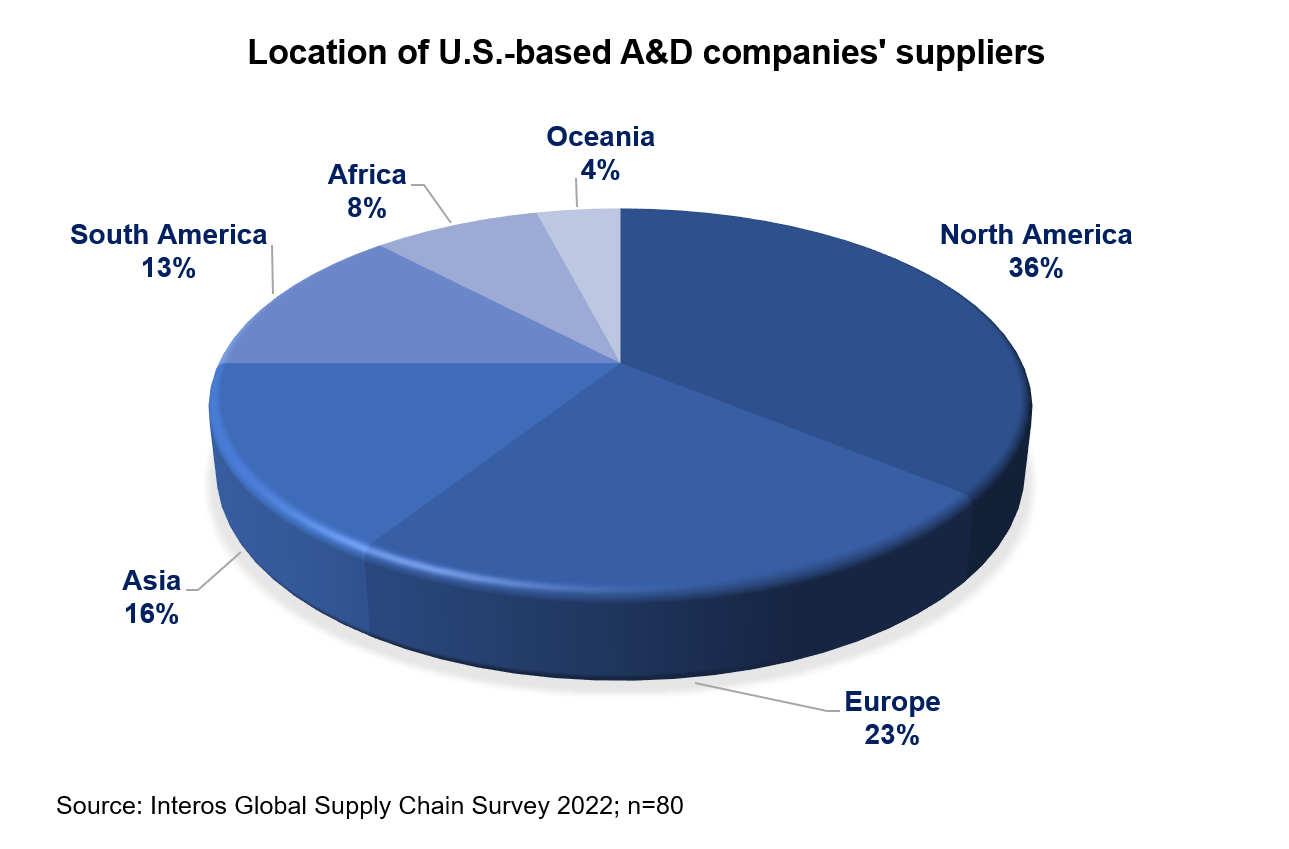

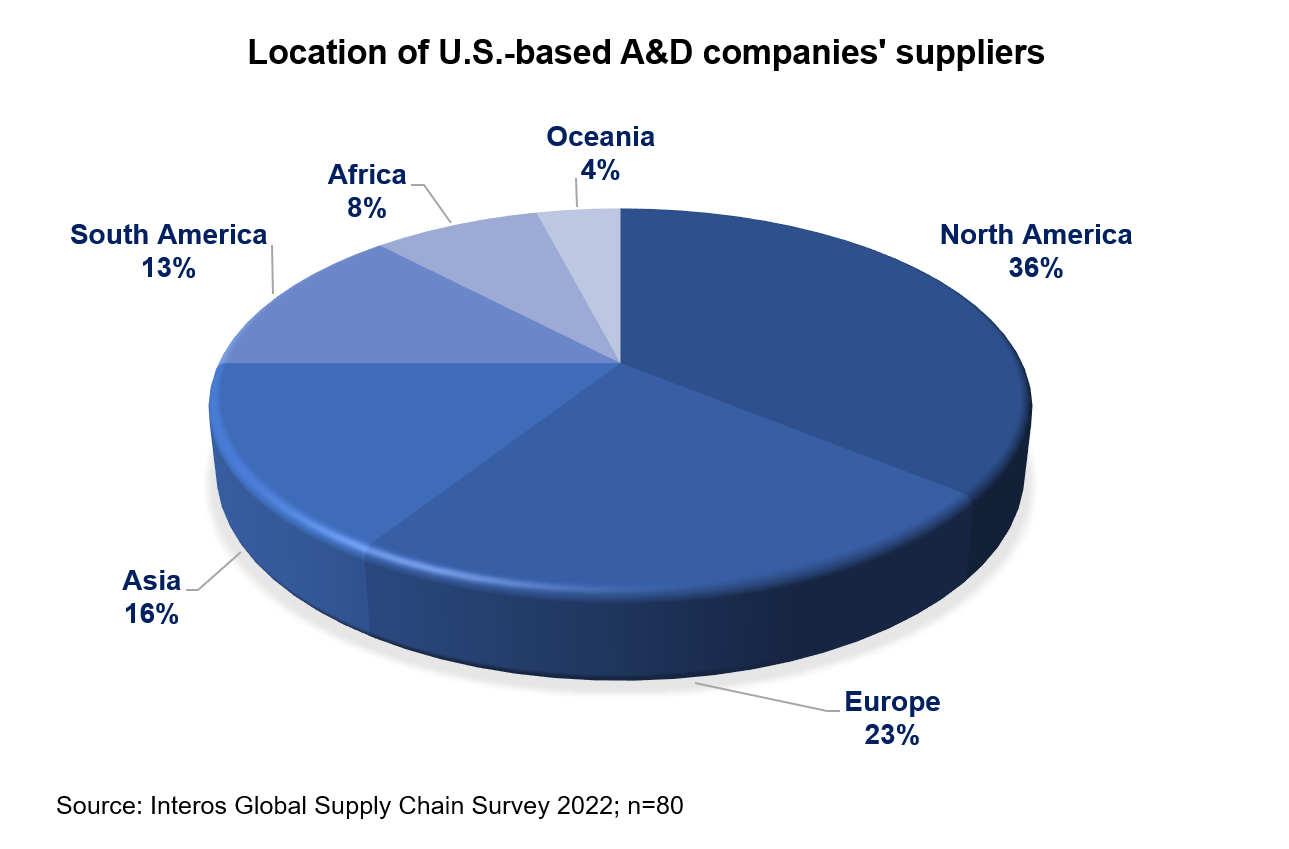

In a survey conducted by Interos in the first quarter of 2022, U.S.-based respondents in A&D said that, on average, almost two-thirds (64%) of their suppliers were located outside North America, with 16% in Asia (see chart below).

They expected just over half (53%) of these contracts to be reshored or nearshored during the next three years.

Public subsidies incentivize regional production

Regionalizing semiconductor manufacturing to reduce over-concentration in Taiwan makes sense to the West for risk diversification and national security reasons — particularly in the light of China’s extensive live-fire military drills in the area following Pelosi’s visit.

Manufacturers such as TSMC, Intel, Samsung, and Micron are being showered with billions of dollars in public subsidies to build fabs in the U.S., buoyed by the recently passed CHIPS and Science Act.

It’s a similar story for the lithium-ion batteries needed to power a new generation of electric vehicles (EVs) and clean energy solutions.

The climate measures of the new Inflation Reduction Act promise over $15 billion in subsidies for EV and other manufacturers to expand capacity within the U.S.

As it stands, this legislation goes further in a bid to reduce dependence on China by withdrawing consumer tax credits from vehicles that contain Chinese battery components (in other words, most of them).

In practice, however, replicating entire supply chains onshore, whether for silicon chips or lithium-ion batteries, is likely to be prohibitive for both cost and time reasons, putting operational resilience in jeopardy.

An in-depth article by Nikkei Asia lays bare the fact that semiconductor supply chains are reliant on a complex network of specialist sub-tier suppliers, not all of whom are going to set up shop next door to shiny new wafer plants.

The U.S. government appears to accept that domestic supply chains have their limits, judging by recent speeches from top officials.

Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen and Trade Representative Katherine Tai are among those who have been busy promoting the virtues of “friendshoring” — doing business only with trusted allies and not authoritarian regimes.

While this concept, and government intervention to support domestic production, seem like sensible strategies to boost supply chain resilience in critical industries, they have come under fire from a number of respected commentators.

Earlier this month, Financial Times trade columnist Alan Beattie questioned whether fashioning an anti-China trading bloc will really be that simple and argued that subsidies and tax credits have the potential to distort markets and increase prices.

And a cover story in The Economist on reinventing globalization warned: “The danger is that a reasonable pursuit of security will morph into rampant protectionism.”

Resilience is about more than security

Where does all of this leave procurement, supply chain, and operational resilience leaders?

For starters, they should be wary of attempts by some politicians and journalists to equate supply chain resilience solely with re/near/friendshoring and national security (including in the otherwise excellent Nikkei article mentioned earlier).

Research by the International Monetary Fund (IMF), discussed in a previous blog, concluded that diversifying sources of supply abroad is a more effective way of building resilience than concentrating it at home.

This finding is supported by a newly published Gartner survey of 400 global supply chain leaders, which found that diversification away from China to other low-cost countries in Asia was more prevalent than nearshoring to developed markets.

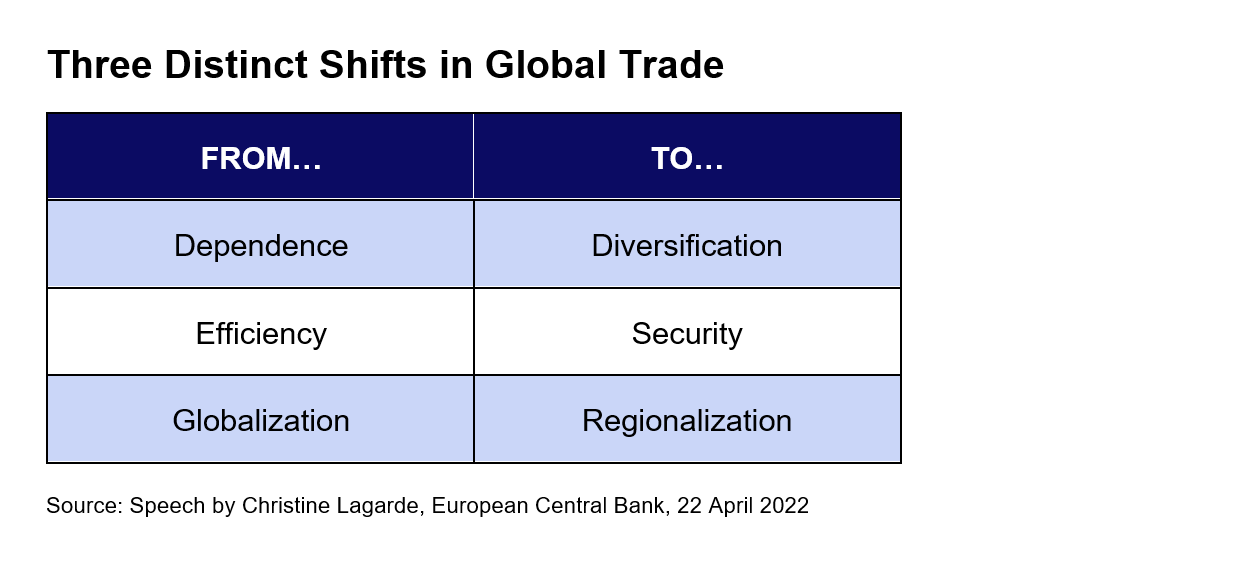

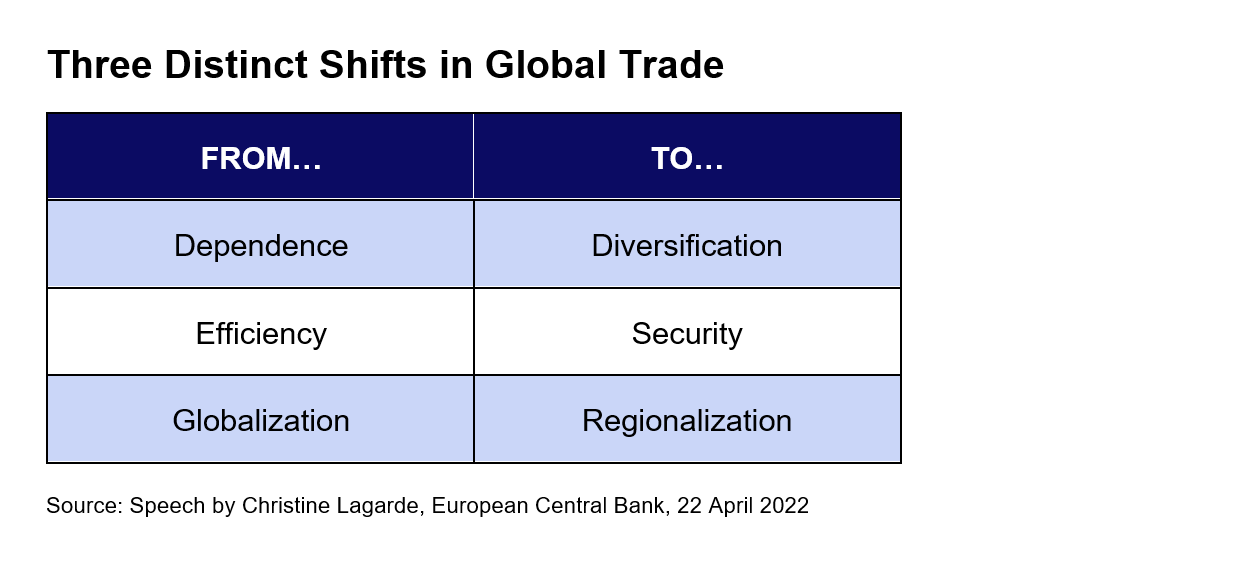

A balanced view of supply chain resilience in a changing trade environment comes from Christine Lagarde, a former IMF boss who is currently President of the European Central Bank.

In a speech in Washington, DC, in April, Lagarde pointed to “three distinct shifts in global trade”:

- Reducing dependence and geographic concentration risk by diversifying suppliers, stockpiling essential materials, and operating “just-in-case” supply chains.

- Focusing less on cost efficiency and more on supply chain security through industrial policies and other government measures.

- Developing regionalized import-export and risk-sharing models where the first-choice “rules-based multilateral trading system” no longer functions effectively.

Lagarde argued that the goal for Europe should be “open strategic autonomy” — defined as striking “a careful balance between insuring against risk in areas where our vulnerabilities are excessive and avoiding protectionism”.

At a time when the benefits of globalization and free trade — including prosperity, innovation, openness, and integration—– are under attack, this is a message that the U.S. and other developed economies would be wise to embrace.

To learn more about how the Interos platform can help your firm face challenges relating to globalization, supply chains, and operational resilience, visit interos.ai.