By Geraint John

These are uncomfortable times for the global elite – which include the politicians, multinational company bosses, and policy wonks who rubbed shoulders at the World Economic Forum’s annual meeting in Davos two weeks ago. A decades-long era of unbridled free trade and globalization – not just core WEF principles, but assumptions on the nature of global economics – has gone into reverse and nations are grappling with rampant inflation, a cost-of-living crisis, and the imminent threat of recession.

No wonder G7 country leaders who would normally have been happy to swap their domestic travails for the fresh air of the Swiss Alps for a few days (Joe Biden, Emmanuel Macron, Rishi Sunak…) opted to stay away this year. As one newspaper commentator put it: “The idea that Davos is faintly toxic has gained ground.”

Nevertheless, plenty of power brokers did attend this first event back in familiar ski-resort surroundings since the pandemic. And in line with the theme of “Cooperation in a Fragmented World”, geopolitical considerations were uppermost in many minds.

“The number one topic here is geopolitics – it’s not the economy,” noted Julie Sweet, CEO of Accenture.

Economic Consequences of Geopolitical Supply Chain Risk

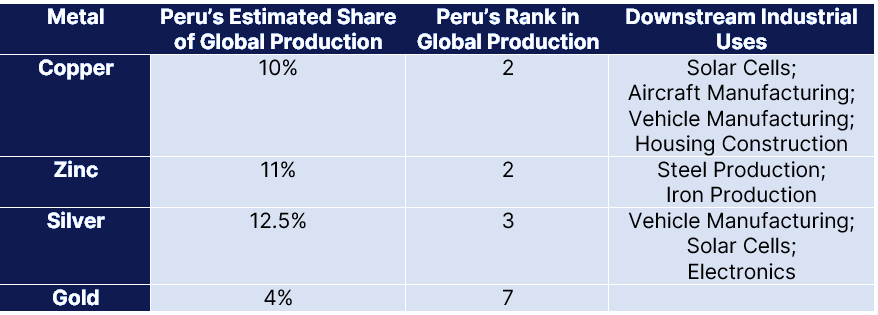

Major sources of concern included growing US technology export controls on and decoupling from China, and tensions between the US, Europe, Japan, and South Korea over aggressive industrial policy that is handing huge subsidies to manufacturers of semiconductors, electric vehicles, lithium-ion batteries and clean-energy solutions on American soil.

It was once again left to China to champion the virtues of globalization (or “re-globalization”) at Davos. “We oppose unilateralism and protectionism, and look forward to strengthening international cooperation,” Vice Premier Liu He told attendees.

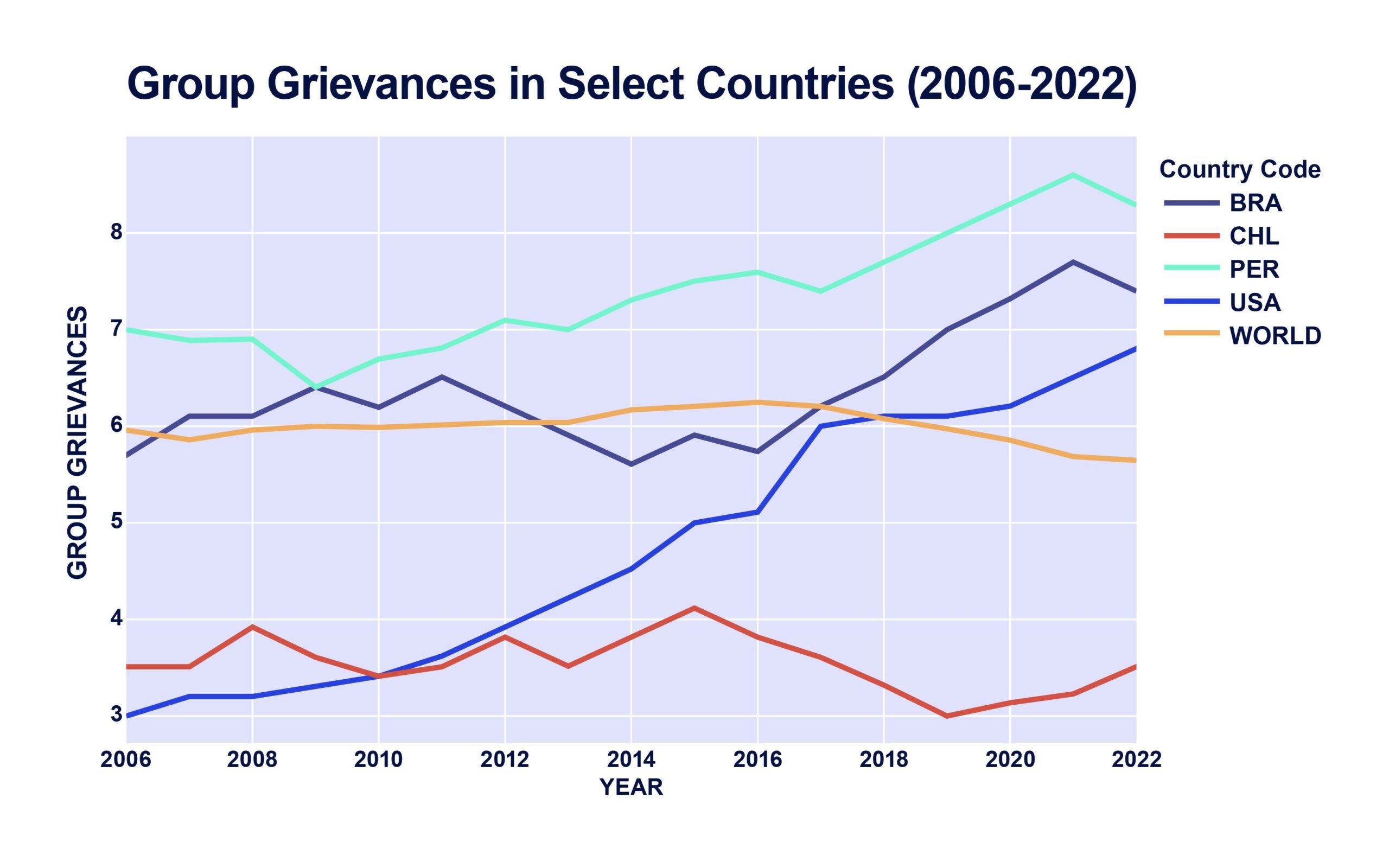

This year’s WEF Global Risks Report, published just before the event, confirms that these tensions are perceived as highly significant for the world economy in the short to medium term, at least. “Geoeconomic confrontation” – which includes sanctions, trade wars and investment restrictions – was ranked third out of more than 30 different types of risk for the next two years by the 1,200 survey participants (see chart).

Fostering greater self-sufficiency in supply chains through state aid and onshoring, and seeking to bolster national security via so-called “friend-shoring” hold dangers for the future, the report warns.

“As geopolitics trumps economics, a longer-term rise in inefficient production and rising prices becomes more likely,” it argues.

Investment in Supply Chain Resilience Remains High Priority at Davos 2023

Resilience in various guises, but particularly operational and supply chain, was also high on the Davos agenda.

Pat Gelsinger, CEO of Intel – which is set to be a major beneficiary of the US government’s subsidies – talked about this in relation to chip shortages. “We needed a global crisis to realize we had allowed ourselves to become dependent on single points of failure in the supply chain,” he told his audience.

“We need resilient supply chains for the future.”

For consultants at McKinsey, this was one of five key takeaways from Davos 2023. “Global disruption isn’t slowing down,” they suggested. “Companies must prioritize building resilience muscles today to prepare for tomorrow.”

That said, business leaders also made it clear they are focused on efficiency, cost discipline and profitability this year. Uber’s CEO, Dara Khosrowshahi, spoke for many when he said: “We have to be much tougher on costs and achieve the same growth plans with a lot less investment.”

This means that investments in supply chain resilience – and in technologies to enable it – need to be carefully weighed and precisely targeted.

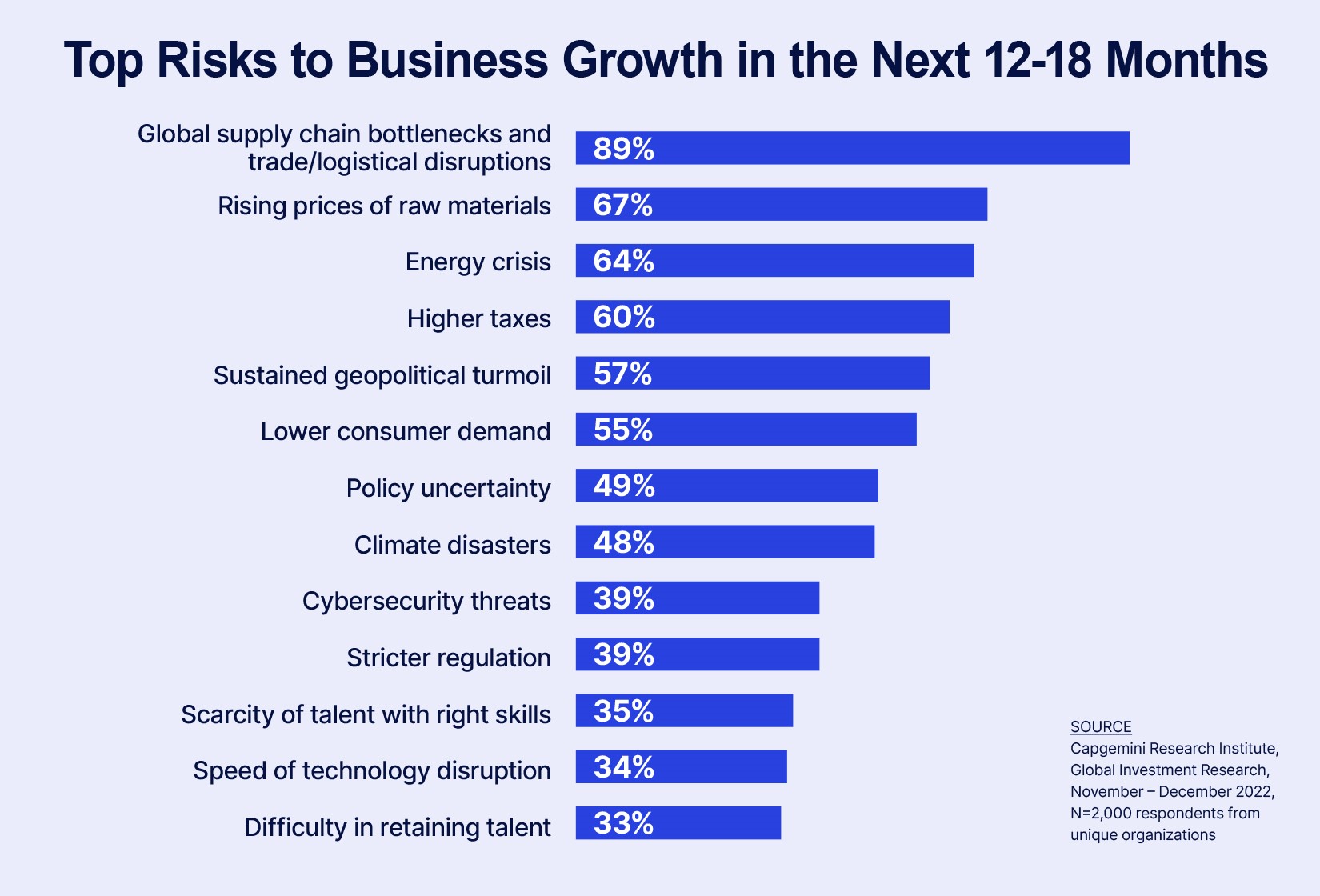

Such sentiments are backed by empirical evidence from a global survey released by Capgemini to coincide with the WEF meeting. Its research among 2,000 executives in a wide variety of roles, geographies and industry sectors found that:

- 89% see supply chain disruptions as the main short-term risk for their organizations – by far the biggest source of risk (see chart).

- 92% of organizations say changes in global supply chains will impact them, but only 15% think they are well equipped to manage this.

- 43% plan to increase their investments in diversifying and digitizing supply chains, on average by more than 10%.

Technologies that aid cost reduction and faster decision making; provide visibility and transparency of supply chains; support supplier and production diversification initiatives; and help to manage trade-offs between cost and service are particularly in demand, according to Capgemini.

In a tough economic climate, investing proactively in operational and supply chain resilience won’t come easy to many companies. But, as WEF President Børge Brende noted in his closing remarks to the Davos meeting: “The cost of inaction when it comes to resilience far exceeds the cost of action.”