By Alberto Coria

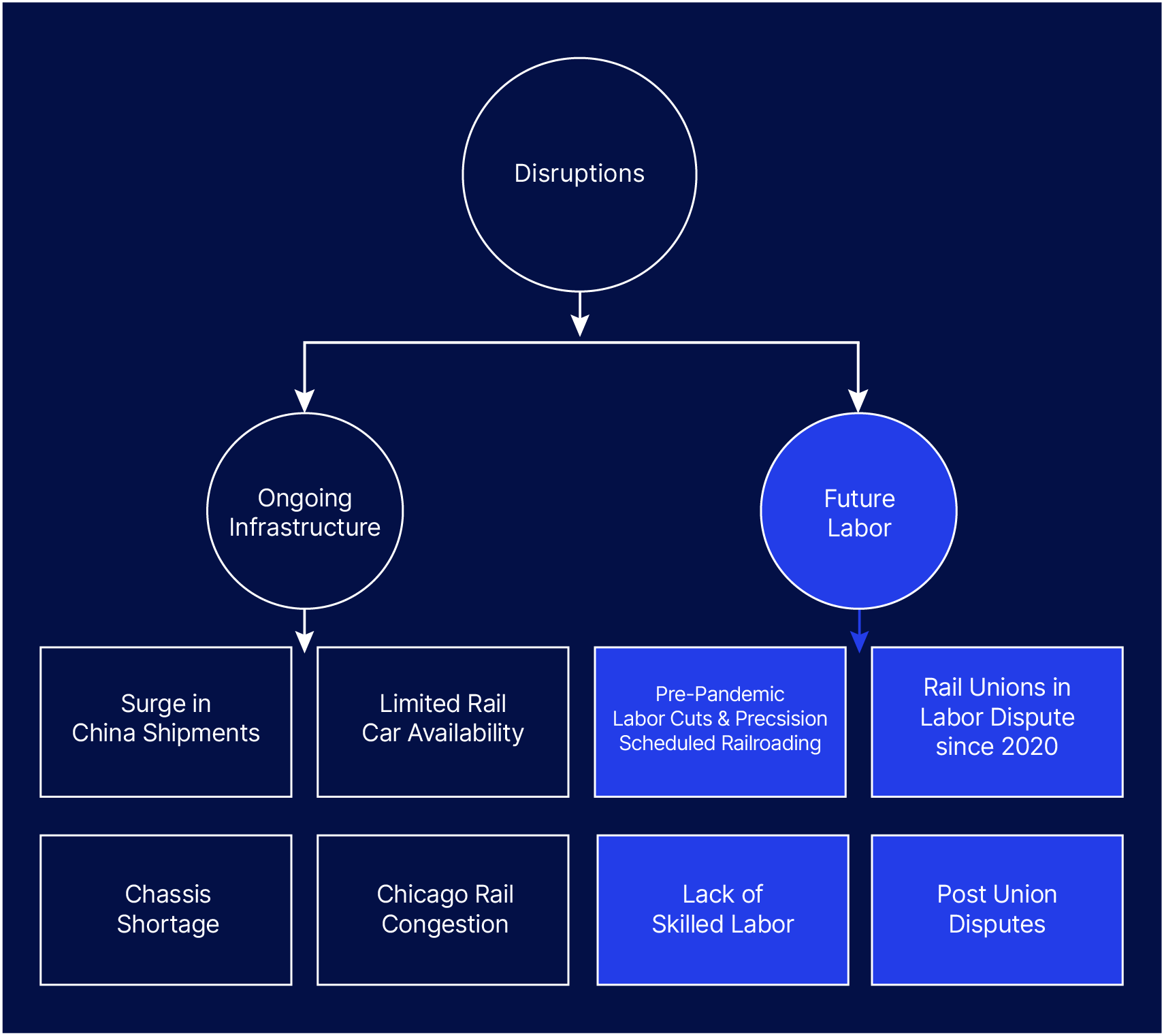

Since 2020, shipping delays have been one of the defining supply chain disruptions of the pandemic era. For several years those delays could be largely attributed to port backups, with cargo ships stuck in long backlogs, waiting to dock and unload containers.

Now, the chokepoint has moved further downstream to the “dwell times” containers are facing at ports before being shipped to warehouses. These dwell times have grown due to a nationwide shortage of intermodal chassis (the unique trailer trucks use to move shipping containers between ports, railways, and shipper facilities) which has caused railyards to become congested and affected their ability to accommodate shipments from ports.

While labor issues have not yet become a critical factor in port or railyard congestion, disputes with unions still linger and pose a potential operational disruption in the future. Understanding the complexity of the situation at U.S. ports is critical for protecting your supply chain, as is investing in resilience-focused technologies that enable insight into that complexity.

In this blog, the analysts from Interos dive deeper into the causes behind increased dwell times, and the ripple effect they’re having across the entire U.S. supply chain.

Infrastructure

U.S. ports have now reduced the backlog of ships waiting in port by an average of 70%, but the issue now lies in dwell times, which is how long goods must sit at ports before they can be transported to warehouses or their final destinations. Due to an ongoing backlog at railroad terminals such as in Chicago, ports don’t have the capacity to move goods out of their ports fast enough once they are unloaded off ships.

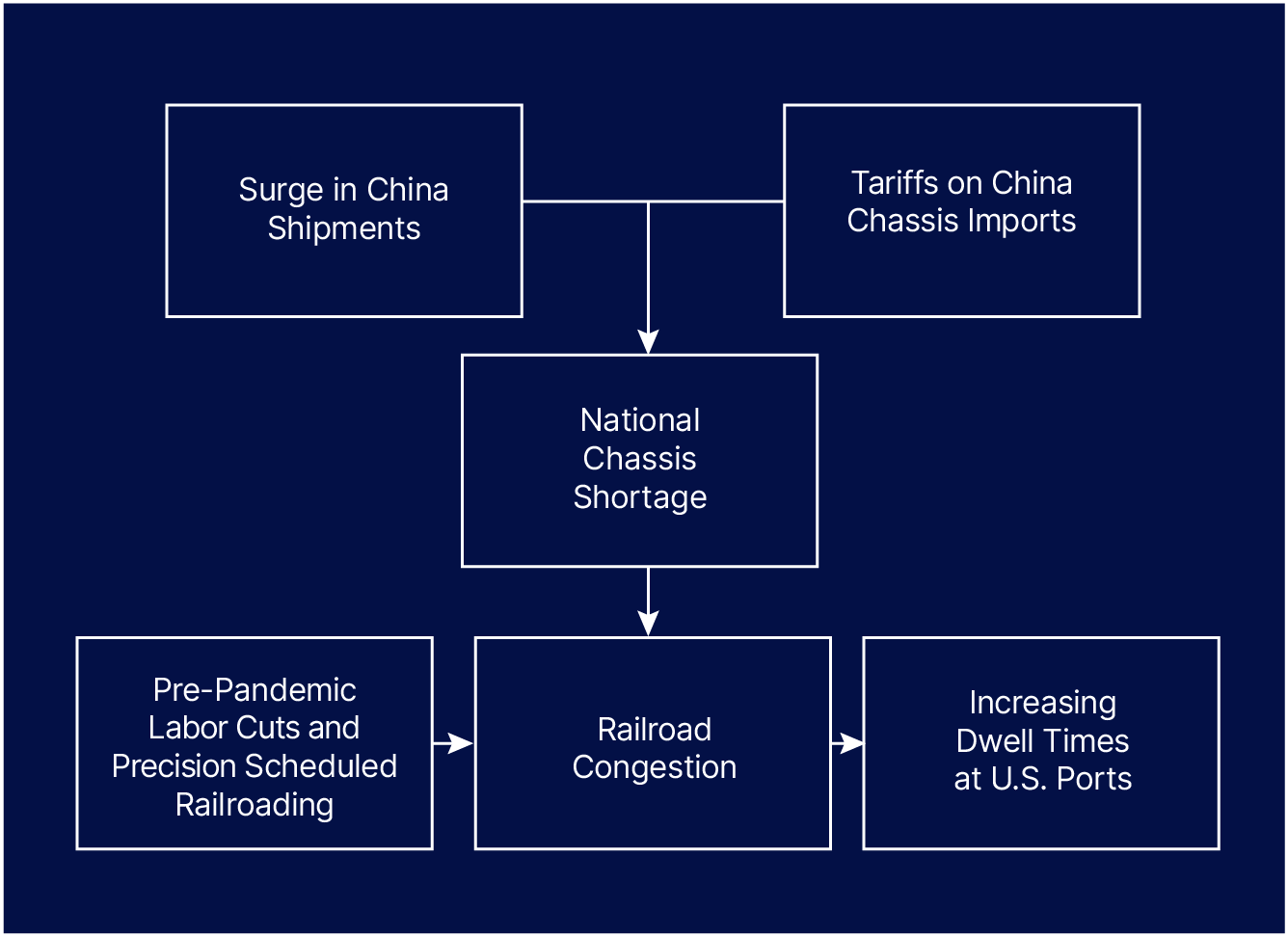

Shortage of Intermodal Chassis

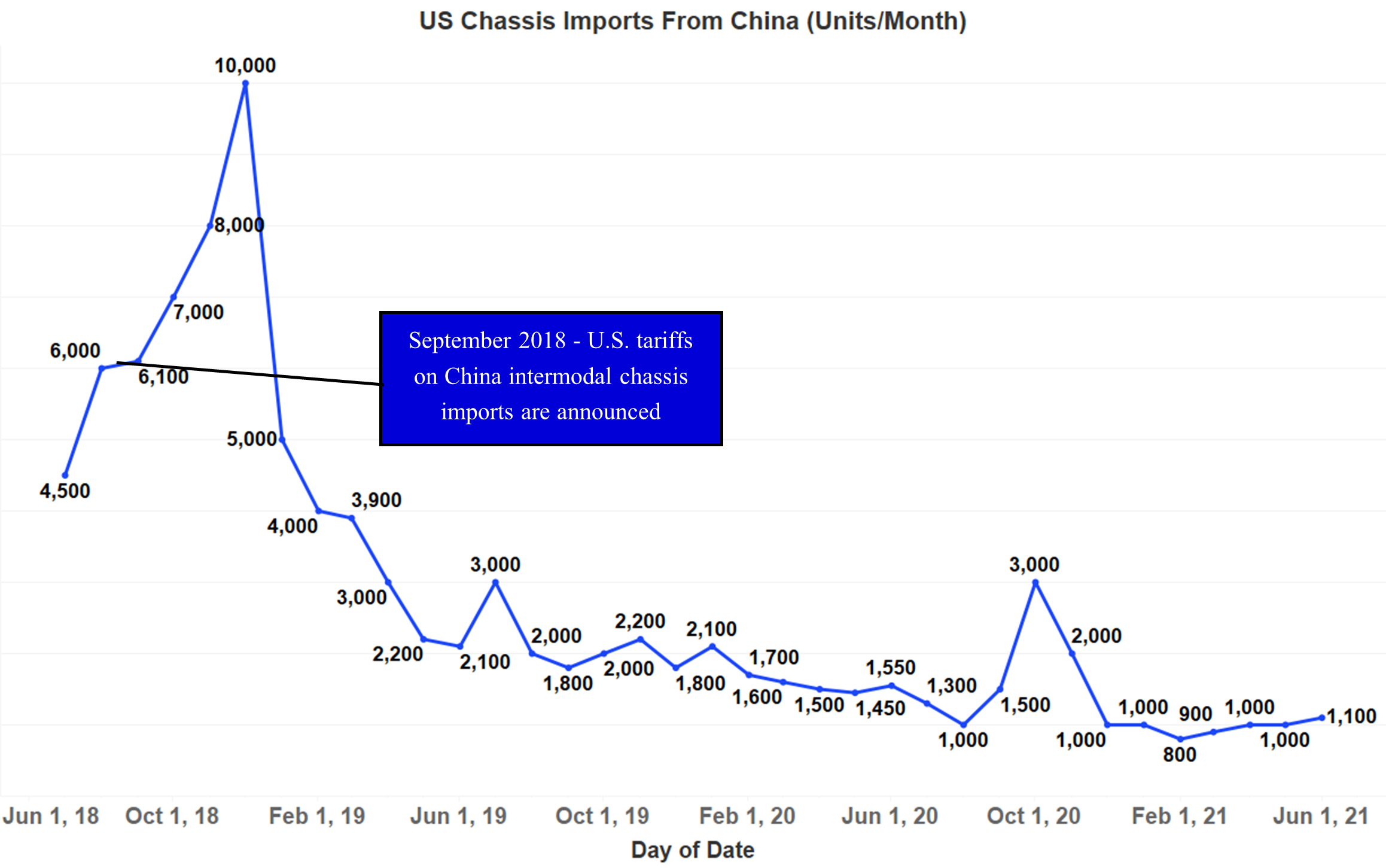

An intermodal chassis is a rubber-tired trailer under-frame on which a container is mounted for truck transport and is necessary to transport containers from ocean or rail to truck. A nationwide shortage of intermodal chassis is one of the key drivers behind rising dwell times at ports. Additionally, a surge in shipments that has elevated the need for intermodal chassis in the U.S. has occurred at the same time as U.S. tariffs have reduced the imports of chassis units from China. The tariffs, which were announced in September 2018, caused chassis imports from China to decrease by 25,000 – 30,000 units in 2019, with American manufacturers failing to increase production at levels needed to replace the lost units.

Surge in China Shipments

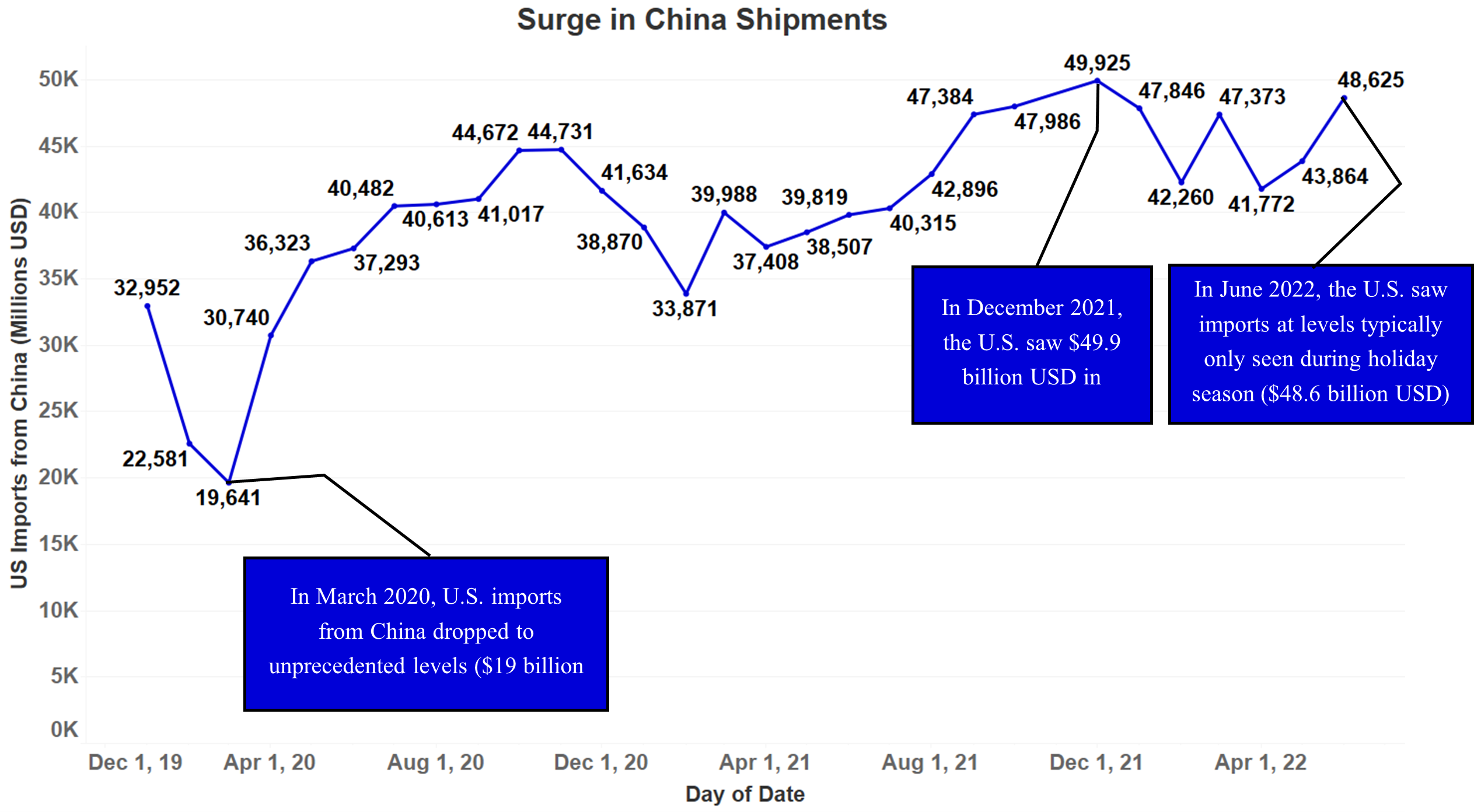

As COVID-19 emerged in China and became a worldwide pandemic in March of 2020, shipments from China to the U.S. dropped. With COVID regulations in the U.S. also beginning to take effect, port labor was furloughed or cut. Once trade resumed, port workers were slow to return to work as shipments began to rise again, creating a backlog of ships waiting to dock at U.S. West Coast ports. This backlog was only reduced to normal levels at the end of Q2 2022.

When the port of Shanghai was under lockdown due to China’s “zero-COVID” policies in May and July of 2022, shipments slightly dropped before surging upwards to levels typically only seen during the holiday season in the U.S. ($48.6 billion USD in June 2022, similar to $49.9 billion USD in December of 2021).

As shipments from China to the U.S. were continuously rising, a surge of imports after the Shanghai port closure occurred at the same time as a national intermodal chassis shortage was occurring in the United States. Railroad terminals had a backlog of containers as they could not find intermodal chassis to offload the containers to trucks, forcing them to reduce shipments from ports, and in turn, causing the dwell time for containers at ports to rise.

Railroad Congestion and Port Dwell Times

Due to the shortage of intermodal chassis in the U.S., railroad terminals such as Chicago are not able to offload their cargo to trucks and have containers sitting on railcars in their terminals, which is, in turn, limiting their ability to take in more shipments from ports.

Chicago’s railyard is the world’s third busiest intermodal hub, where nearly a quarter of the U.S.’ rail shipments arrive or pass through. Chicago is also one of the nation’s prime distribution hubs, as it is within a 500-mile journey of about one-third of the U.S. population. With Chicago playing such an important role within the freight railroad ecosystem, its congestion is one of the key drivers behind the rising dwell times at key U.S. ports such as LA, Long Beach, Savannah, New York, and Charleston.

Another issue causing Chicago’s railyard to experience such high congestion has been a pandemic-driven decrease in the number of rail workers, while railroad operators simultaneously moved to implement precision-scheduled railroading (PSR). PSR is a strategy for railroads to drive more efficient operations on fixed schedules, with the intent to use fewer railcars, and fewer terminals, and provide predictable and reliable service. However, the PSR implementation effectively made railroad operators unable to deal with fluctuations in the supply chain, and with the recent surge of shipments from China, the industry has found itself to have a shortage of equipment to deal with the surge.

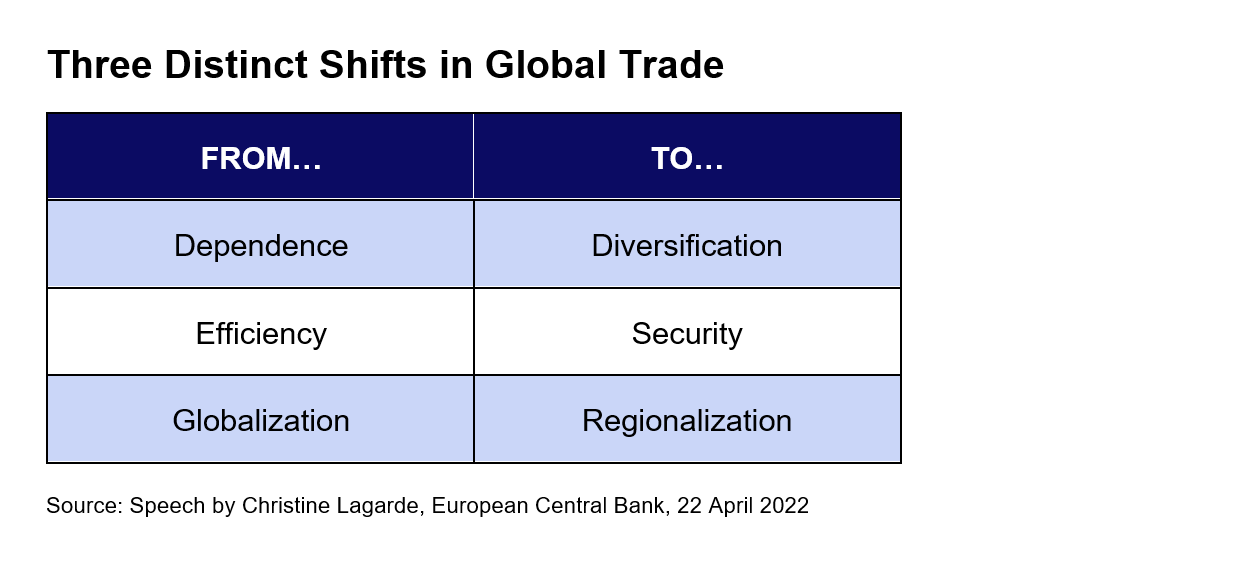

In some ways, PSR is a microcosm of the bigger-picture supply chain problems created by the dominant Just-in-Time (JIT) inventory/operational model that has dominated international trade and manufacturing for the past forty years. The JIT model also leverages highly precise scheduling and demand forecasting to minimize storage and shipment costs, prioritizing efficiency over most other metrics for success. Like PSR, the JIT model similarly buckled under the unpredictable demand spikes crated by COVID. Taken together, the failure of both of these systems makes the case that resilience must demand equal or even greater priority than efficiency.

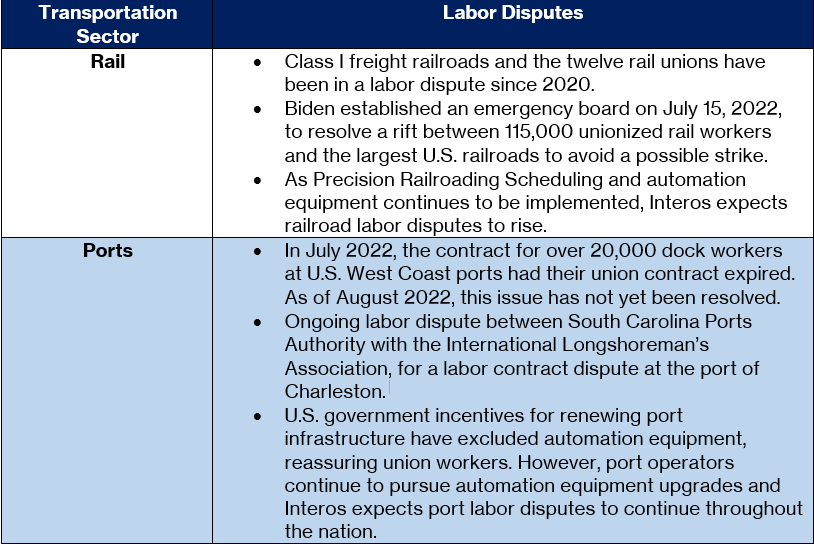

Labor Issues

In contrast to the ongoing infrastructure issues causing port and railyard congestion, labor disputes for both industries appear to be negotiated in good faith by port and rail operators. The majority of labor disputes are regarding port or rail operators seeking to purchase equipment that increases the level of automation in their operations, and therefore threatens the jobs of union workers. As government investment into U.S. infrastructure increases, it is likely that the number of unions filing labor disputes against proposed automation will increase. Interos recommends continuous monitoring of these labor disputes.

Current Labor Market

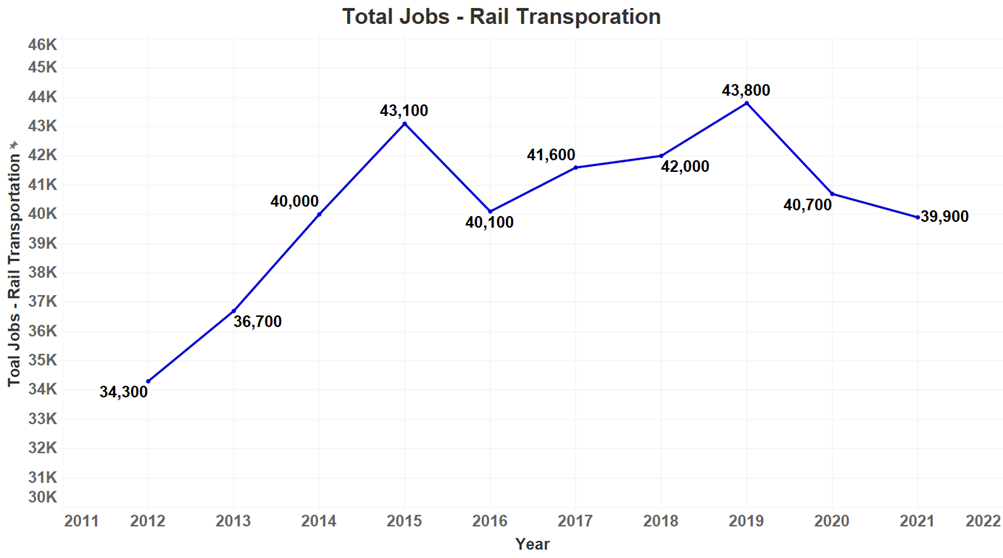

Interos analyzed official employment data from the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics from 2012 – 2021 and found the data suggests that employment in 2020 dropped significantly since 2019 due to the COVID-19 pandemic, but it is not yet at a level of critical risk.

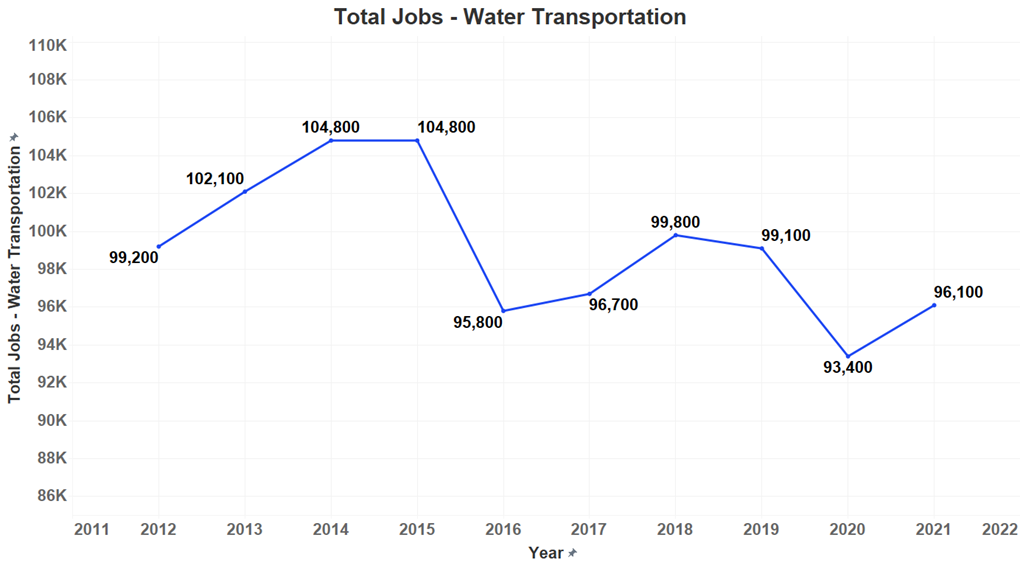

Interos also analyzed employment data for port labor for the years 2012-2021 and found the data suggests that employment levels for port workers dropped significantly since 2019 due to the COVID-19 pandemic but is not yet at a level of critical risk.

Potential Outcomes

The chokepoint causing congestion at ports and railyards has moved downstream from backlogs of ships waiting to dock to long dwell times and overflowing railyards. The congestion is also now apparent at ports throughout the U.S. as opposed to just being a West Coast port problem as it was in 2020 and 2021. Interos has modeled three hypothetical scenarios representing possible outcomes:

Best: Government-funded infrastructure projects are implemented quickly, and U.S. intermodal chassis producers meet demand within 6-12 months. The long dwell times and congested railyards are likely to diminish within 12 months in this scenario.

Moderate: Government-funded infrastructure projects are implemented within 2-3 years and U.S. intermodal chassis producers meet demand within 12-18 months. The long dwell times and congested railyards are likely to diminish within two years in this scenario.

Worst: Government-funded infrastructure projects take over 4 years to be implemented, U.S. intermodal chassis producers meet demand within 2-3 years, and the port and rail unions implement a labor strike. In this scenario, the long dwell times and congested railyards are likely to continue for up to four years before diminishing.

Conclusion

Despite massive reductions in cargo ship backups, major U.S. ports and railyards still face significant delays due to supply chain issues surrounding intermodal chassis availability, a workforce that is still slowly recovering from COVID-driven layoffs, and the adoption of new railyard technologies that prioritize efficiency over resilience.

Despite popular belief, labor disputes currently have relatively little influence over these delays, though that may change as both the implementation of — and opposition to — automated port and rail technologies increases.

With enough government investment in critical infrastructure, and a more widespread adoption of resilience-focused approach to operations alongside the technologies that enable it, these delays could be greatly reduced within a matter of twelve months. However, a failure to do so will likely mean continued shipping delays for many U.S. industries and consumers.

To learn more about the potential impacts of supply chain disruptions and what companies are doing about it, check out our annual industry survey, Resilience 2022.